SHAN PEOPLE AND THEIR CULTURE

SHAN is the Burman appellation for those races who call themselves Tai (တႆး).

They are probably the most numerous and widely diffused Indo-Chinese race and occupy the valleys and plateaus of the broad belt of mountainous country that leaves the Himalayas and trends Southeasternly between Burma proper on the west and China, Assam, and Cambodia on the east, to the Gulf of Siam.[1]

The Origin of Dai/Tai/Shan

TAI

Tai are people of mainland Southeast Asia, including:

The Thai or Siamese (in central and southern Thailand),

The Lao (in Laos and northern Thailand),

The Shan (in northeast Myanmar @ Burma),

The Dai (in Yunnan province, China, Myanmar, Laos, northern Thailand and Vietnam) and

The Tai (in northern Vietnam).

Some historians claim that the Tai people were, in BC 3000, the inhabitants of Asia, the central part of the land now known as China.[2] Rev. William C. Dodd, a Christian missionary, stated that the Tai settled in the land now known as China before the Chinese arrived, based on Chinese annals of 2200 BC.[3] The history of contact between the Tai and Han (Chinese) peoples dates back to 109 BC, when Emperor Wu Di of the Han Dynasty set up Yizhou Prefecture in southwestern Yi (the name used to signify the minority areas of what are now Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces). The Tai, in subsequent years, sent tribute to the Han court in Luoyang; among the emissaries were musicians and acrobats. The Han court gave gold seals to the Tai ambassadors and their chieftain the title “Great Captain.” According to Chinese documents of the ninth century, the Tai had a fairly well-developed agriculture. They used oxen and elephants to till the land, grew large quantities of rice, and built an extensive irrigation system. They used kapok for weaving, panned salt, and made weapons of metal. They plated their teeth with gold and silver. [4]

Why Tai are also called Shan?

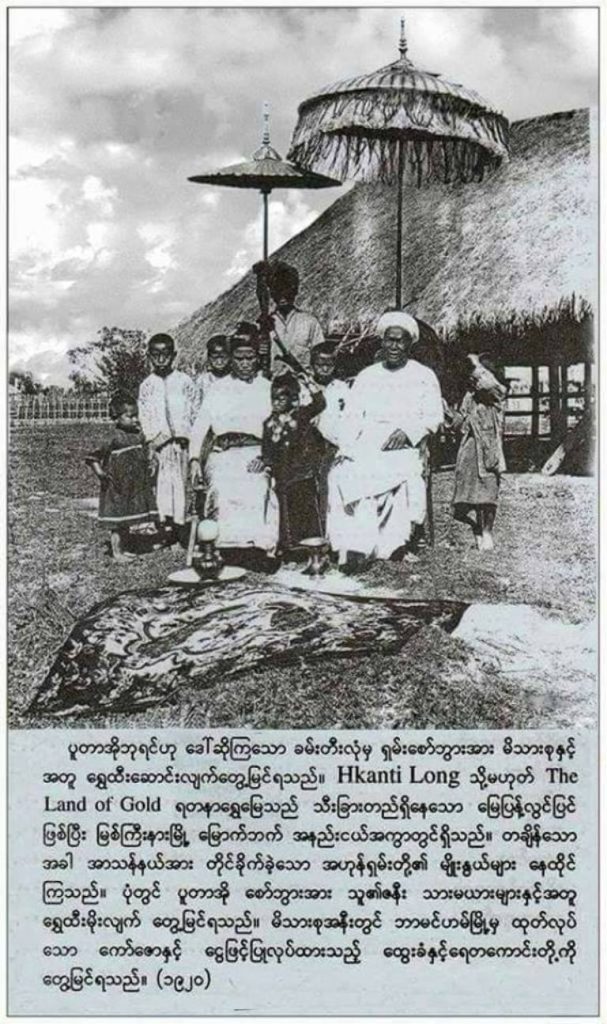

One of the suppositions concerning the origin of the name “Shan” (ရှမ်း) is that it derived from the word “Siam” (Hsian, Sein), which designates a group of mountainous people who migrated from Yunnan in the 6th century AD. Siam means agriculture or cultivating. Most probably because they were people of farming. Another supposition is, when Kublai Khan and his Mongol army conquered the Nan Chao Kingdom in AD 1253, a second wave of Tai migrated down south into many areas of Southeast Asia. Some migrating Tai became mercenaries for the Khmer armies in the early 13th century AD, as it was depicted on the walls of Angkor Wat. In those days, the Khmer called Tai as Syam, the word derived from the Sanskrit word meaning golden or yellow. The Tai at that time had a yellow or golden skin color. Shan can be a corrupt word of Syam, a name given to Kshatriya (warriors) (those warriors were said to be Shan) who were on duty for the Khmer Empire. A third supposition suggests that Shan were the people named after the “Great Mountain Ranges of China” from where they had migrated. Shan in Chinese is “mountain” or “hill”.[10]

According to Chinese annals, the “Ta Muong” (Great Muong) lived in the northwestern part of Szechuan province, in western central China, even before the Chinese migrated from the west. Ta Muong would have been the ancestors of the “Ai Lao” or “Tai” race known as Pa, Pa Lao, or PaYi in China, who later founded the powerful “Nan Chao Kingdom” in Yunnan province. In BC 1558, the Tai had spread over a vast territory, almost across the whole width of modern China. Tai have never been called Chinese, nor claimed to have any ethnic links with the Chinese race. Throughout Chinese historical records, the Chinese name for the Tai has constantly been changed.[5] According to American Missionary Rev. William W. Cochrane, Tai means Free.[6] Sometimes it is also written as Dai when referring to Tai in China. The Dai ethnic group in China, with a population of about 1.2 million, mainly lives in Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Region and Xishuangbanna (SipSongPanNa), which means twelve productive rice fields, Autonomous Prefecture, in the southern part of Yunnan province. The main Dai groups in China are Dai Lu, Dai Nua, and Dai Mao. According to Travel China Guide, Dai is the name of the nationality, which means “freedom”.[7] Tai or Shan is now used as a generic word to cover the whole race, spelled by the French as Thay. The name is said to mean “The Free” or “Free Men.”[8] Why do they call themselves “Tai” or “Free” or “Freedom” or “Freemen”? Most likely, according to the history of Tai people, they were under attack many times by many groups such as Monkhmer, Mongol, and Chinese for centuries. Their Kingdoms had been destroyed, Kingdom by Kingdom. They were dispersed to many places in Southeast Asia because of the war. They ended up “people without a country” in other countries such as China, Burma, India, and Vietnam, and became a minority group of people in those countries. They would long for freedom. The great Tai race, who number today about 100 million, had established numerous Kingdoms and States in the past and still governs the two nations of Thailand and Laos. Tai people consider Thailand and Laos as Tai countries that exist today.[9]

Tai in Burma are called Shan. But Shan always call themselves Tai (တႆး) . Shan population in Burma is about 5 million (10% of Burma total population)[11]

The Ancient Kingdoms

Shan had their country and ruled by King since BC 2000 up to 16th Century AD when the last Shan kingdom was overthrown by Burman King Bayinnaung. There were nine Shan kingdoms recorded in early history.

- Tsu Kingdom (မိူင်းသု/မိူင်းသိူဝ်) (BC 2000 – BC 222)

- Ai Lao Kingdom (မိူင်းဢၢႆႈလၢဝ်း) (AD 47 – AD 225)

- Nan Chao Kingdom (မိူင်းလၢၼ်ႉၸဝ်ႈ) (AD 649 – AD 1252)

- Muong Mao Lone Kingdom (မိူင်းမၢဝ်းလူင်) (AD 764 – AD 1252)

- Yonok Kingdom (မိူင်းလၢၼ်ႉၼႃး) (AD 773 – AD 1080)

- SipSongPanNa (မိူင်းသိပ်းသွင်ပၼ်းၼႃး) (AD 1180 – AD 1292)

- Waisali Kingdom (မိူင်းတူၼ်ႈသွၼ်းၶမ်း) (AD 1227 – AD 1838)

- Sukhothai (မိူင်းထႆး) (AD 1238 – AD 1350)

- Muong Mao Kingdom (မိူင်းမၢဝ်း) (AD 1311 – AD 1604)

Muong Mao Kingdom was the last kingdom of Tai/Shan.

The Kings of MuongMao

Hsu Kan Hpa (သိူဝ်ၶၢၼ်ႇၾ) (AD 1311 – AD 1364) (founder of Muong Mao)

Hsu Pem Hpa (သိူဝ်ပိမ်ႇၾ) (AD 1364 – AD 1366)

Hsu Wak Hpa (သိူဝ်ဝၢၵ်ႇၾ) (AD 1366 – AD 1367)

Hsu Hzun Hpa (သိူဝ်ၸိုၼ်ၾ) (AD 1367 – AD 1368)

Hsu Hom Hpa (သိူဝ်ႁူမ်ႇၾ) (AD 1367 – AD 1371)

Hsu Yap Hpa (သိူဝ်ယဵပ်ႇၾ) (AD 1371)

Hsu Hum Hpa (သိူဝ်ႁူမ်ၾ) (AD 1372 – AD 1405)

Hsu Ke Hpa (သိူဝ်ၶီႇၾ) (AD 1405 – AD 1420)

Their Migration

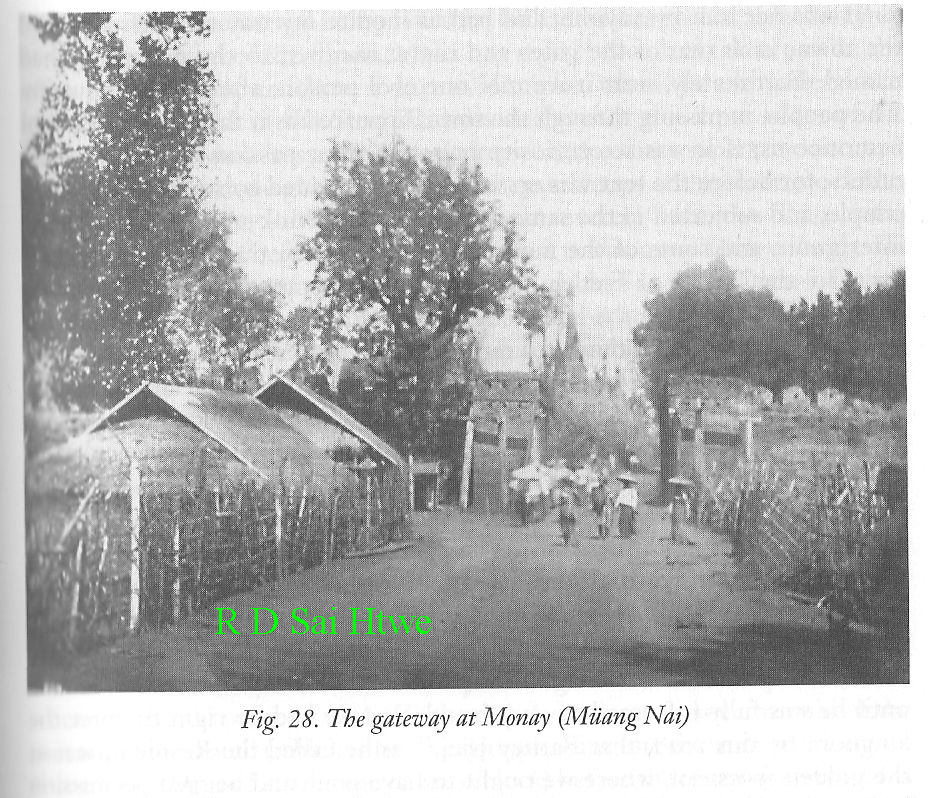

Shan’s first migration was said to take place in the 1st century BC when wars in central China drove many Tai people from that area. Those people moved South founded ancient Shan cities such as “MuongMao” (မိူင်းမၢဝ်း) “MuongNai” (မိူင်းၼၢႆး) “HsenWi” (သႅၼ်ဝီ) and “HsiPaw” (သီႇပေႃႉ). All of them are in Burma today. The second migration occurred in the 6th century AD from the mountain of Yunnan. They followed “Nam Mao River” (ၼမ်ႉမၢဝ်း) (ShweLi River) to the South and settled in the valleys and regions surrounding the river. Some continued west into Thailand. A second branch went north following the Brahmaputra River into Northern Assam, India. These three groups of Tai migrants were: Tai Ahom (Assam), Siam (Thailand), and Shan (Shan State), who came to regard themselves as “Free People.”[12]

Their Present Settlement

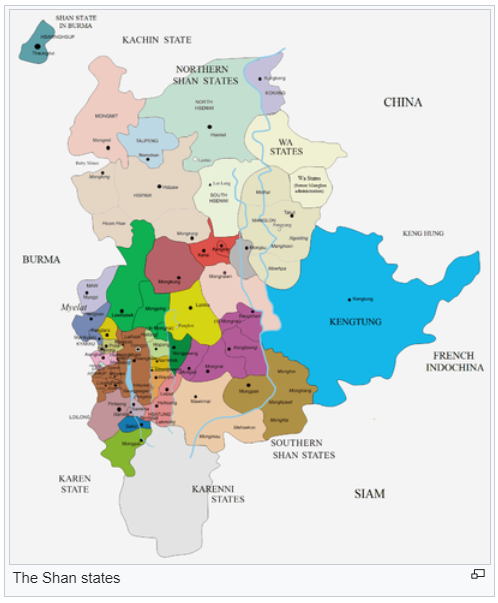

Shan State in Burma

Shan live in Burma, China, India, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam under different names but always one and the same people in different countries.

Tai people in Burma are called Shan. There are five million Shan in Burma. Their land is called Shan State. Shan people in Burma are also known as Tai Lone, Tai Lai, Dai Nua, Dai Mao, Tai Dome, Tai Ding, Tai Sa, Tai La, Tai Wan, Tai Hume, Tai Lamm, Tai Kwan, Dai Lu, Tai Sam Tao, Tai An, Tai Khun, Tai Ngam, Tai Hai Ya, Tai Yang, Tai Loi, Tai Leng, Tai Khamti.

In China, about ten million Shan live in Yunnan, Hainan, and Guangdong. They are known as Dai. There are three main Tai groups in China such as Dai Nua, Dai Mao, and Dai Lu. Other Tai groups in China are known as Dai Yangze, Dai Nam (Sue Dai) or Dai Nung, Dai Lai, Dai Lone, Dai Chaung, Dai Doi, Dai Lung, Dai Kai Hua Jen, Tuo Law or Pa Yi, Pu Tai, Pu Naung, Pu Man, Pu Yu, Pu Chia, Pu En, Pu Yai, Pu Sui, Dai Ching, Dai Pa, Dai Tu Jen, Dai Doi, Dai Tho, Dai Hakkas, Dai Ong Be, Dai Li or Dai Lo.

In India Tai live in Assam State. They are known as Tai Ahom or Tai Assam or Tai Khamti.

တိုင်းအဟုမ် (Tai Ahom) လူမျိုးများ အာသံပြည် (Assam) ကို ၁၂၂၈-၁၈၃၈ ( ၆၁၀ နစ် ) ထိ အုပ်ချုပ်မင်းလုပ်ခဲ.ပါတယ်။

အာသံပြည် (Assam) ဟာ အခု အိန္ဒိယပြည် (India) လက်အောက်ခံပြည်နယ်ဖြစ်နေပါတယ်။

Ahom Dynasty ……………

1 Sukaphaa 1228–1268

2 Suteuphaa 1268–1281

3 Subinphaa 1281–1293

4 Sukhaangphaa 1293–1332

5 Sukhrangpha 1332–1364

Interregnum 1364–1369

6 Sutuphaa 1369–1376

Interregnum 1376–1380

7 Tyao Khamti 1380–1389

Interregnum 1389–1397

8 Sudangphaa 1397–1407

9 Sujangphaa 1407–1422

10 Suphakphaa 1422–1439

11 Susenphaa 1439–1488

12 Suhenphaa 1488–1493

13 Supimphaa 1493–1497

14 Suhungmung 1497–1539

15 Suklenmung 1539–1552

16 Sukhaamphaa 1552–1603

17 Susenghphaa 1603–1641

18 Suramphaa 1641–1644

19 Sutingphaa 1644–1648

20 Sutamla 1648–1663

21 Supangmung 1663–1670

22 Sunyatphaa 1670–1672

23 Suklamphaa 1672–1674

24 Suhung 1674–1675

25 Gobar Roja 1675–1675

26 Sujinphaa 1675–1677

27 Sudoiphaa 1677–1679

28 Sulikphaa 1679–1681

29 Gadadhar Singha 1681–1696

30 Sukhrungphaa 1696–1714

31 Sutanphaa 1714–1744

32 Sunenphaa 1744–1751

33 Suremphaa 1751–1769

34 Sunyeophaa 1769–1780

35 Suhitpangphaa 1780–1795

36 Suklingphaa 1795–1811

37 Sudingphaa 1811–1818

38 Purandar Singha 1818–1819

39 Sudingphaa 1819–1821

40 Jogeswar Singha 1821–1822

41 Purandar Singha 1833–1838

In Lao they are known as Lao-Tai, include local groups such as Black Tai (Tai Dam) (Dai Lum) and Red Tai (Tai Deng) (Tai Leng) and Tai Nua.

In Thailand they are known as Tai Yai, literally means Great Tai (တႆးယႂ်ႇ) .

In Vietnam they are known as Black Tai (တႆးလမ်ႊ) and White Tai (Tai Khao) (တႆးၶၢဝ်) numbering about five hundred thousand. Some other Tai in Vietnam are; Tai Tho (တႆးထူဝ်), Tai Nung (တႆးၼူင်), Tai To Tis (တႆးထူဝ်ႉတိ), Tai Yang or Tai Nhang (တႆးယၢင်း/တႆးၼၢင်း), Tai Leng (တႆးလႅင်ႊ), Tai Pong Toa (တႆးၽွင်းထူဝ်), Dai Lu (တႆးလိူဝ်ႉ).

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the estimated total number of Tai in the late 20th century is about 75,760,000 (including 45,060,000 Thai in Thailand, 3,020,000 Laotians in Laos, 3,710,000 Shan in Burma, 21,180,000 Dai in China, and about 2,790,000 Tai in Vietnam)[13] (Tai in India, Assam State, are not included in this statistic)

Climate and Natural Resources in Shan States

The lands where the Shan live today are called the Shan States. There are three seasons in a year; summer, raining and winter. Normally summer begins in March and ends in June, raining season begins in July and ends in October and winter begins in November and ends in February. Shan State has the most pleasant weather in Burma.

There are rich natural resources in the Shan States. The most produced agricultural product of the Shan States is rice. Other important agricultural products include tea, cigar wrapping leaf, coffee, orange, potato, tomato and cabbage, garlic, indigo, wheat, strawberry, pear, pineapple, cotton, tobacco, and a variety of vegetables. Among forest products, teak is the most important. The principal cottage industry in the Shan States is weaving products. Shan do not grow opium. The mining resources in Shan States produce jade, silver, lead, gold, copper, iron, wolfram, tin, tungsten, manganese, nickel, coal, antimony, mica, marble, and zinc. It is even called “God’s Own Country”[14]

The most famous mines in Shan States are;

NamTu Mine

YaTaNaTheinKe Mine

HaeMawSai Mine

HaeGalaw Mine

HaeLoiMa Mine

HinKao Mine

HtanPaiNgak Mine

The great silver mine in NamTu (Bawdwin) was supposed to be the second largest in the world.[15] There are forests in the areas with an altitude of 3,000 feet above sea level in the Shan States. Bamboo grows naturally in the forests with trees such as Kyun (teak), Pyingadoe, Padauk, In, Kanyin, and other hardwoods. Shan States have over 2,000,000 acres of forest reserve, over 1.5 million acres of cultivated areas consisting of over 500,000 acres for paddy and crops cultivation, about 200,000 acres for hillside cultivation, over 8,000 acres of land formed by the process of silting for cultivation, and over 200,000 acres for gardens.

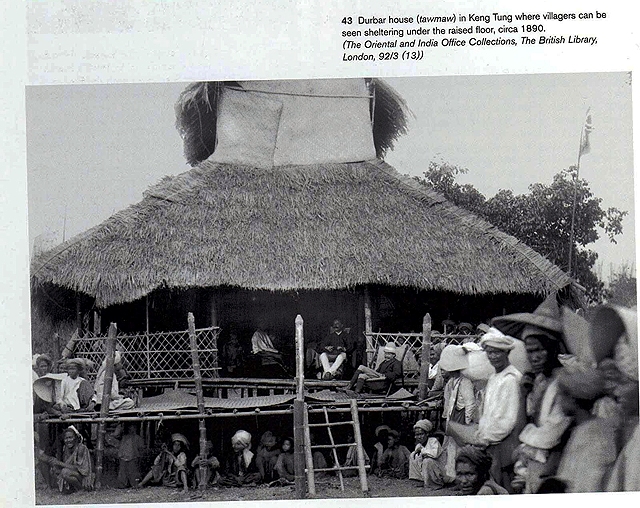

Political History

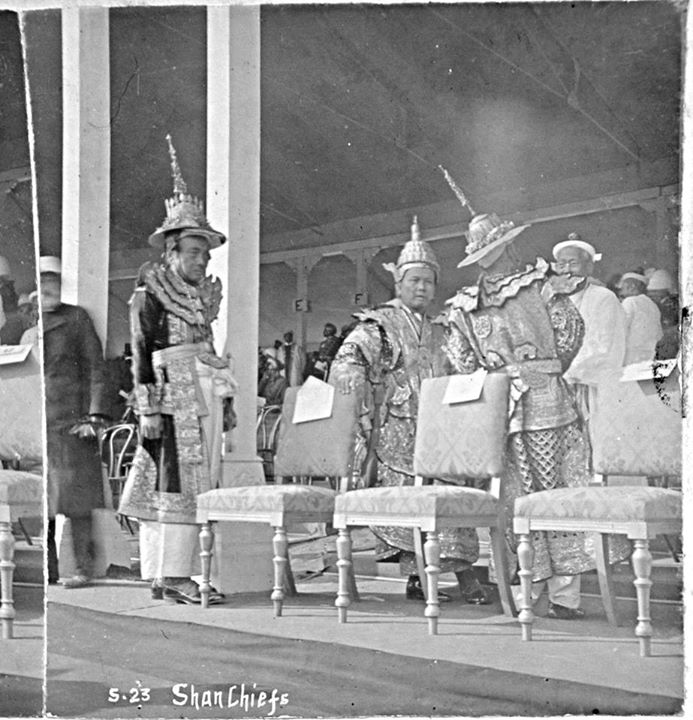

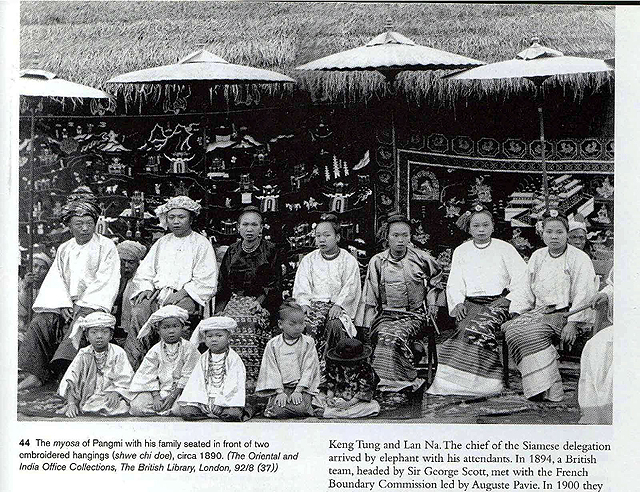

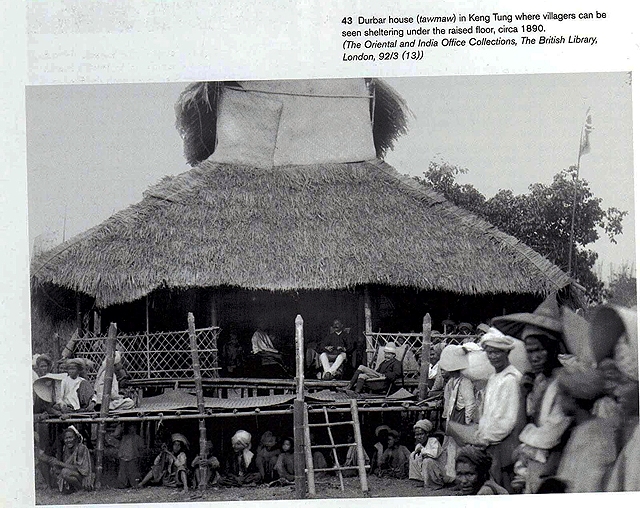

After the last Shan Kingdom, Muong Mao Kingdom, was overthrown by the Burman King, Ba Yint Noung, in AD 1560 Shan fragmented countries were governed by SaoPha (Shan chief) appointed by the Burman King. Burman King allowed SaoPha to rule their regions, but they had to pay allegiance to the Burman central court. From the middle of the 19th century onwards, the Burman authority imposed greater control through the stationing of military officers, sitke or bhomu, to impose regular payments of allegiance to the central treasury.[16] The holder of the authority over the town was known as MyoSa (literally means town eater). MyoSa was assigned to collect revenues on behalf of the Burman king.[17]

In AD 1765 there were 12 Shan territories.

AD 1782-1819 there were 188 towns and 5,885 villages in Shan territories.

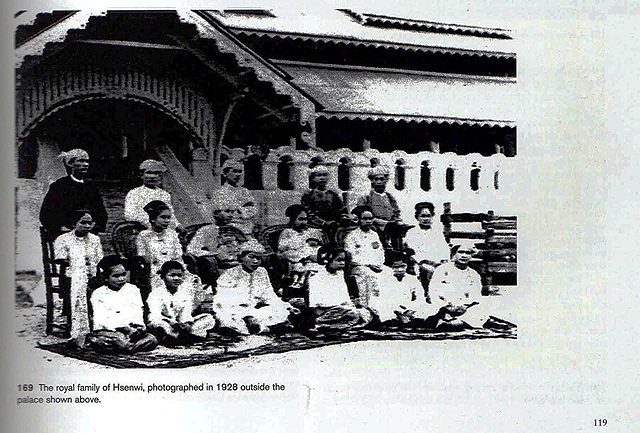

Before the Second World War, 14 SaoPha were ruling Shan territories.

AD 1824-26; First Anglo-Burmese war ended with the “Treaty of Yandabo”, according to which Burma ceded the Arakan coastal strip between Chittagong and Cape Negrais to British India.

AD 1852 Britain annexed lower Burma, including Rangoon, following the second Anglo-Burmese war. The defeat of the Burman troops in the second Anglo-Burmese war led to more significant political and administrative changes.

AD 1885-86; Britain captured Mandalay after a brief battle and Burma became a province of British India. Mandalay fell and King ThiBaw and his queen SuPhaYaLat were taken to Ratanagir near Bombay.

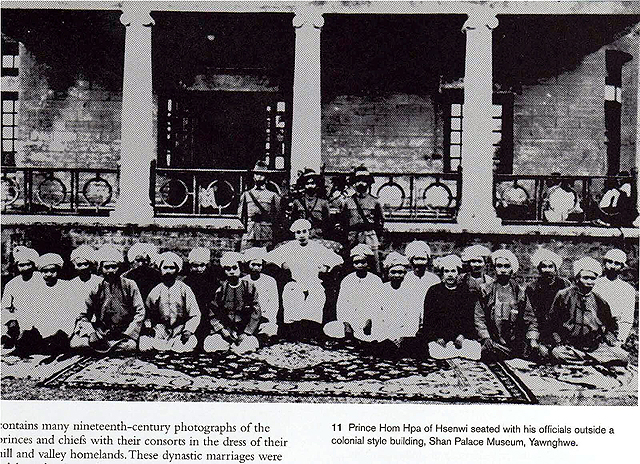

Britain annexed Shan States in 1887. The Shan States were administered separately from Burma with SaoPha.

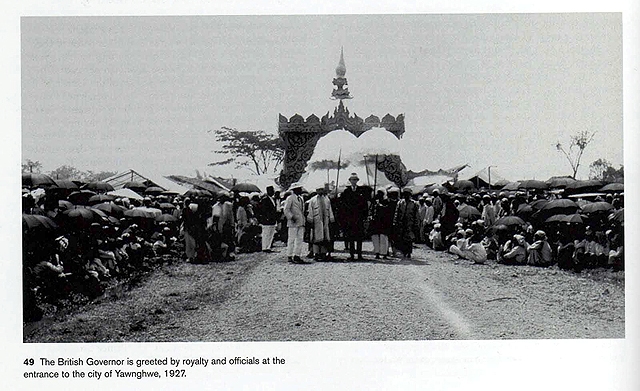

The Shan States under British (1887-1948)

After the annexation of Shan countries by the British in 1887, the British sought to govern Shan countries and their people through SaoPha. SaoPha had to acknowledge British supremacy, maintain peace, and not oppress their subjects. Between 1887 and 1895, the SaoPha pledged their allegiance to the British crown, and their domains were placed under the supervision of British Assistant Superintendents.[18]

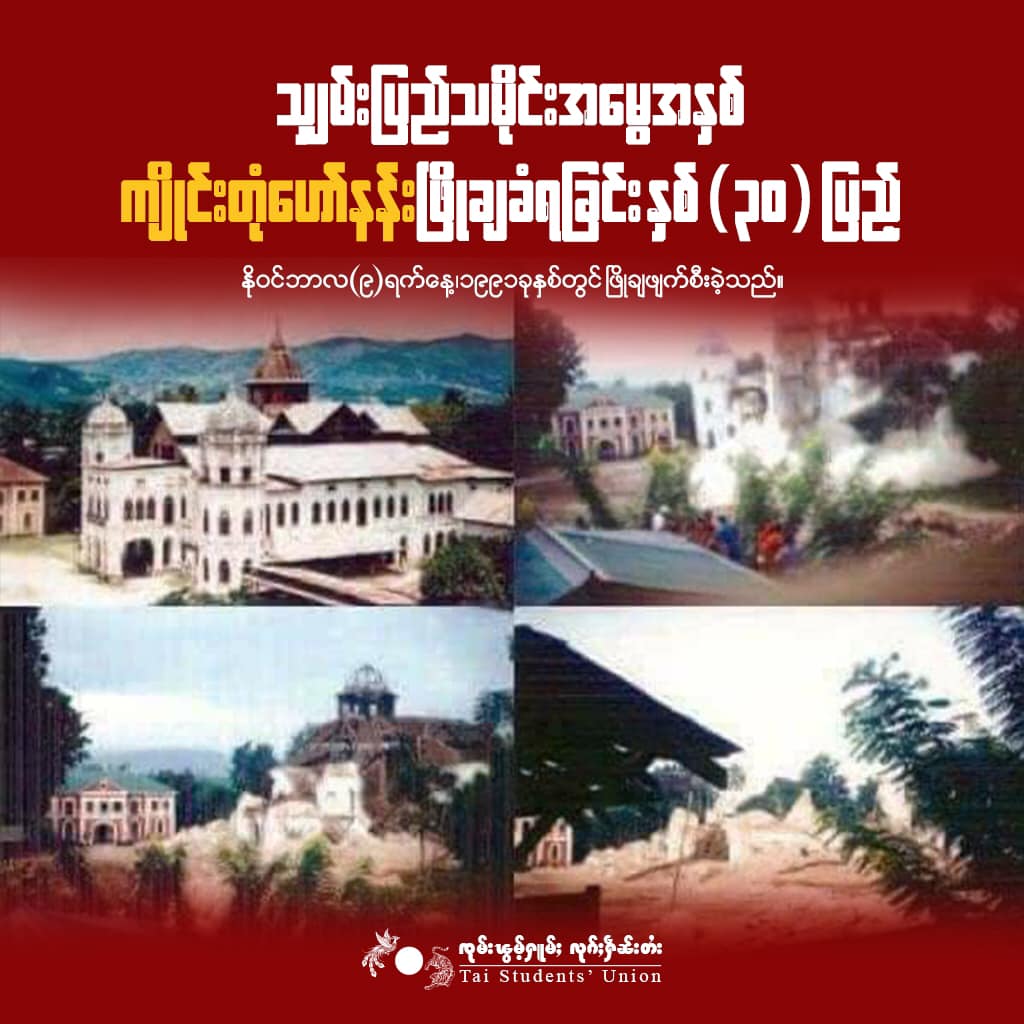

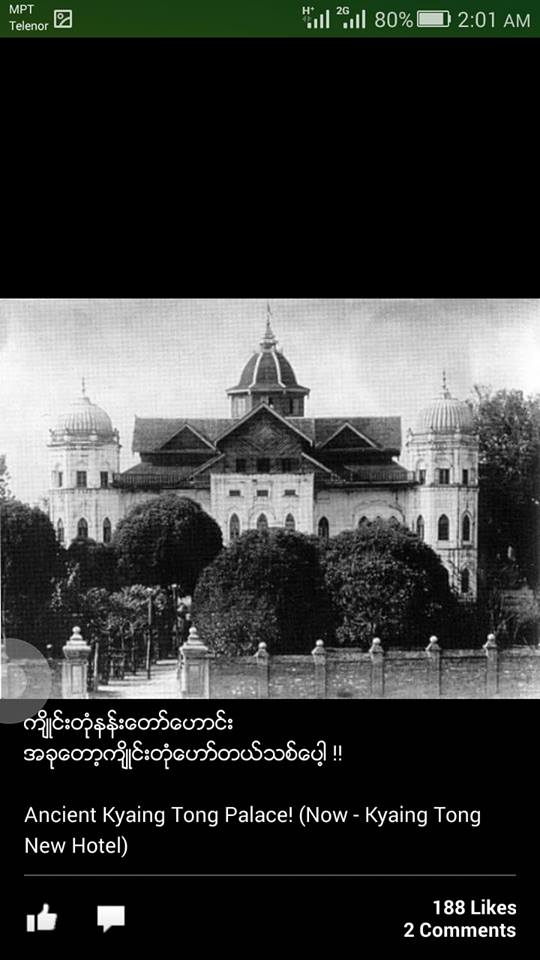

The formal administrative entity known as the “Federated Shan States” was not created until 1922. Under the British government, the 40 Shan States were combined and then divided into three general sections: the Northern Shan State, the Southern Shan State, and the Eastern Shan State; altogether, they formed the “Federated Shan State”. Federated Shan State was formed under the British colony on October 1, 1922. There are three Shan States until today. All these Shan States gained independence on January 4, 1948, together with other States, but they are all now under the Burma Military Government since 1962.

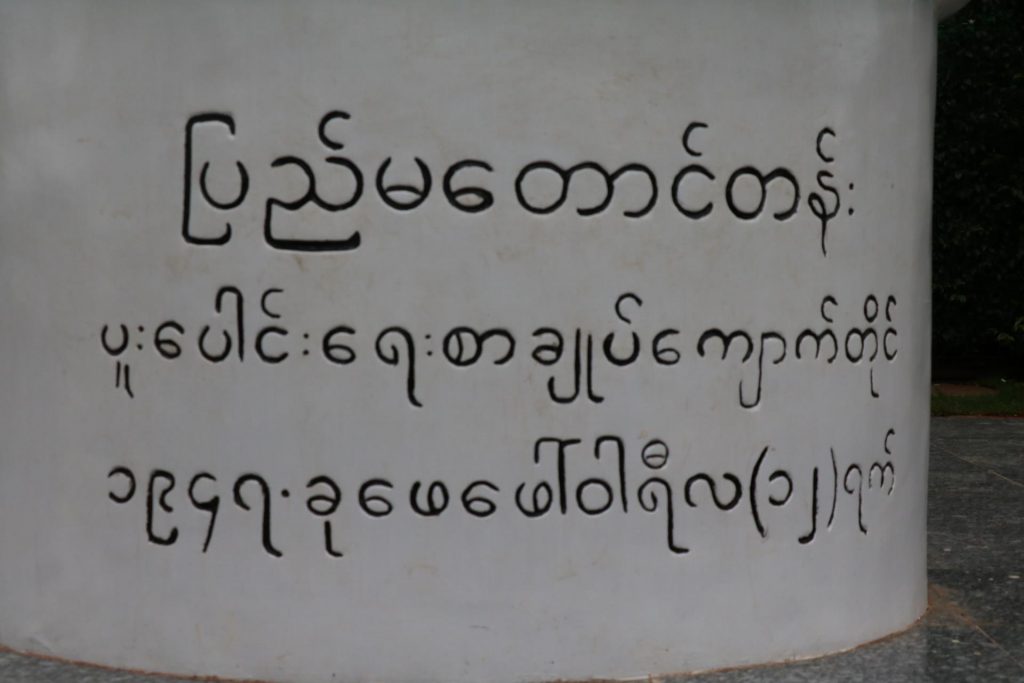

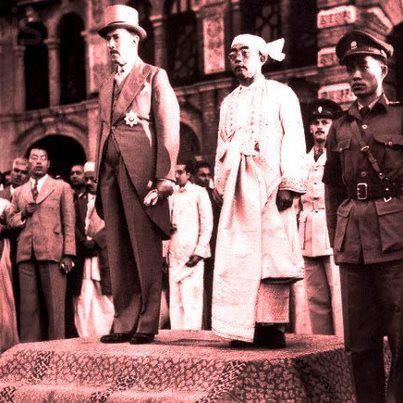

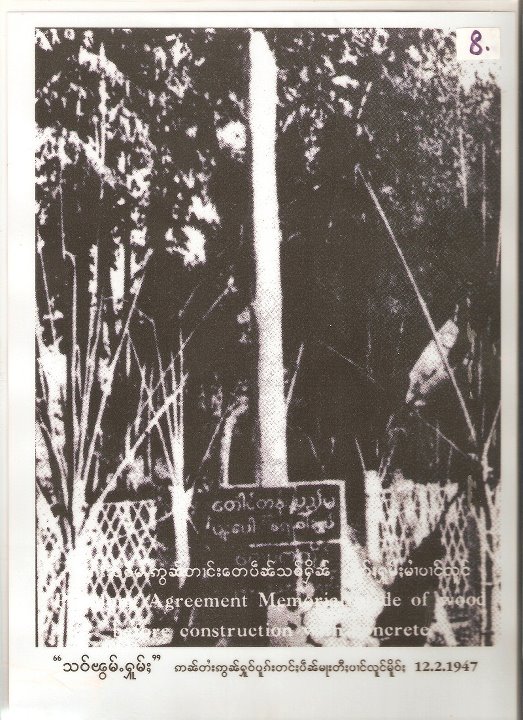

PangLong Agreement

Before meeting with General Aung San, all the Shan leaders and people of the Shan States got together to adopt the Shan Flag and the National Anthem. February 7, 1947 was marked as Shan National Day. A conference held at PangLong, Southern Shan State, attended by General Aung San, members of the Executive Council of the Governor of Burma, all SaoPha and representatives of the Shan States, Kachin Hills and Chin Hills on February 10, 1947.

General Aung San explained to the Shan SaoPha that he was going to London very soon and was asking for independence. He also wanted the Shan States to be independent at the same time.[20] The Members of the conference believed that freedom would be more speedily achieved by the cooperation of Shan, Kachin, and Chin with the Interim Burmese Government.

Agreement [21]

(I) A representative of the Hill Peoples, selected by the Governor on the recommendation of representatives of the Supreme Council of the United Hill Peoples, shall be appointed a Counselor to the Governor to deal with the Frontier Areas.

(II) The said Counselor shall also be appointed a member of the Governor’s Executive Council without portfolio, and the subject of Frontier Areas brought within the purview of the Executive Council by constitutional convention, as in the case of Defence and External Affairs. The Counselor for Frontier Areas shall be given executive authority by similar means.

(III) The said Counselor shall be assisted by two Deputy Counselors representing races of which he is not a member. While the two Deputy Counselors should deal in the first instance with the affairs of the respective areas and the Counselor with all the remaining parts of the Frontier Areas, they should, by Constitutional Convention, act on the principle of joint responsibility.

(IV) While the Counselor in his capacity of Member of the Executive Council will be the only representative of the Frontier Areas on the Council, the Deputy Counselor(s) shall be entitled to attend meetings of the Council when subjects pertaining to the Frontier Areas are discussed.

(V) Though the Governor’s Executive Council will be augmented as agreed above, it will not operate in respect of the Frontier Areas in any manner which would deprive any portion of these Areas of the autonomy which it now enjoys in internal administration. Full autonomy in internal administration for the Frontier Areas is accepted in principle.

(VI) Though the question of demarcating and establishing a separate Kachin State within a Unified Burma must be relegated for decision by the Constituent Assembly, it is agreed that such a State is desirable. As a first step towards this end, the Counselor for Frontier Areas and the Deputy Counselors shall be consulted in the administration of such areas in the Myitkyina and the Bhamo District as are Part 2 Scheduled Areas under the Government of Burma Act of 1935.

(VII) Citizens of the Frontier Areas shall enjoy rights and privileges which are regarded as fundamental in democratic countries.

(VIII) The arrangements accepted in this Agreement are without prejudice to the financial autonomy now vested in the Federated Shan States.

(IX) The arrangements accepted in this Agreement are without prejudice to the financial assistance which the Kachin Hills and the Chin Hills are entitled to receive from the revenues of Burma and the Executive Council will examine with the Frontier Areas Counselor and Deputy Counselor(s) the feasibility of adopting for the Kachin Hills and the Chin Hills financial arrangements similar to those between Burma and the Federated Shan States.

Signatories of PangLong Agreement

The 23 signatories of the PangLong Agreement were consisted of 14 Shan, 5 Kachin, 3 Chin and 1 Burman.

One from Burman Committee,

(1) General Aung San

Five from Kachin Committee,

(1) Samma Duwa Sinwa Naw (rep. from MyitKyiNa)

(2) Duwa Zau Rip (rep. from MyitKyiNa)

(3) Dingra Tang (rep. from MyitKyiNa)

(4) Duwa Zau Lawn (rep. from WanMaw a.k.a BhaMo)

(5) Labang Grong (rep. from WanMaw a.k.a BhaMo)

Three from Chin Committee,

(1) U Hlur Hmung (rep. from FaLam)

(2) U Thaung Za Khup. (rep. from TidDim)

(3) U Kio Mang. (rep. from HaKa)

Fourteen from Shan Committee,

(1) Khun Pan Sing. (SaoPha Lone of TawngPeng State)

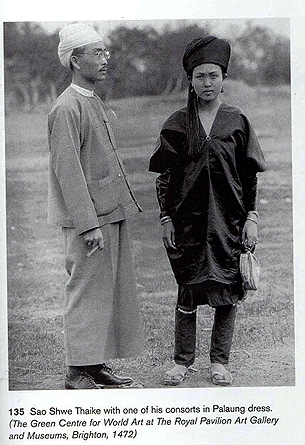

(2) Sao Shwe Thaike (SaoPha Lone of YawngHwe State)

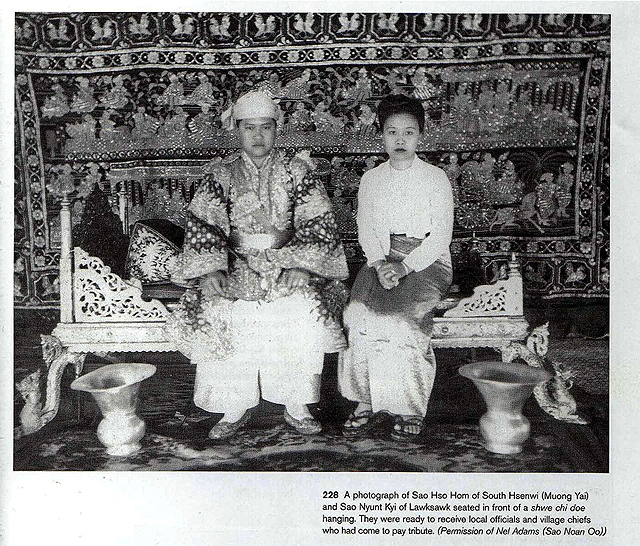

(3) Sao Hom Hpa. (SaoPha Lone of North HsenWi State)

(4) Sao Num. (SaoPha Lone of LaiKha State)

(5) Sao Sam Htun (SaoPha Lone of MuongPawn State)

(6) Sao Htun E (SaoPha Lone of HsaMongHkam State)

(7) U Phyu (rep. of HsaHtung Saophalong)

(8) U Khun Pung (SPFL) (Shan People Freedom League)

(9) U Tin E (SPFL)

(10) U Kya Bu (SPFL)

(11) Sao Yape Hpa (SPFL)

(12) U Htun Myint (SPFL)

(13) U Khun Saw (SPFL)

(14) U Khun Htee (PangLong) (SPFL)

Based on this foundation, the Union of Burma was established.

February 12, 1947, the day of the signing of the agreement, is marked as Union Day.[22]

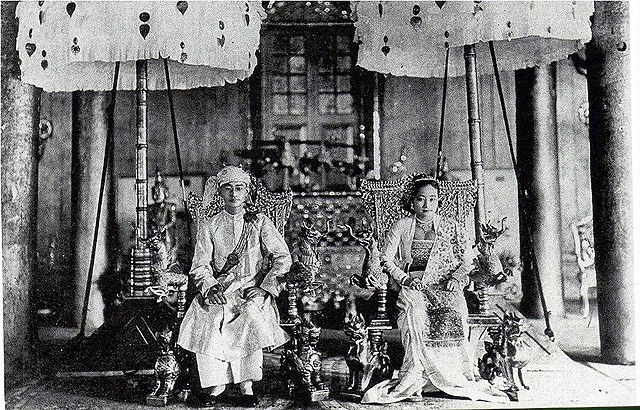

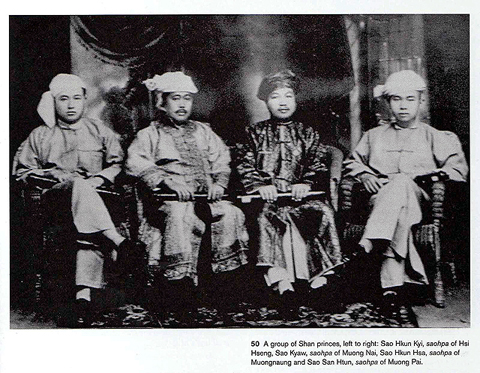

Independence of Burma and Shan SaoPha ( ၸဝ်ႈၾ )

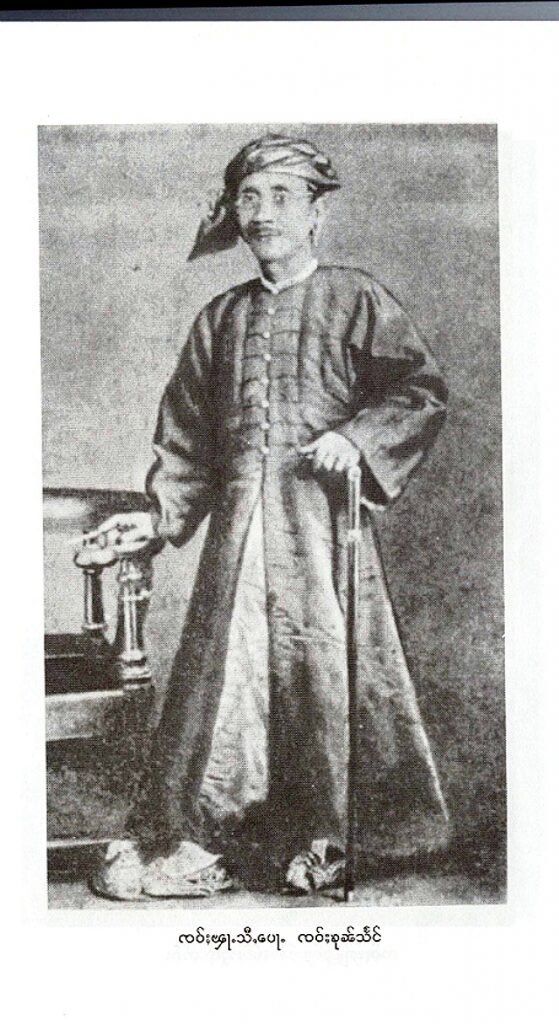

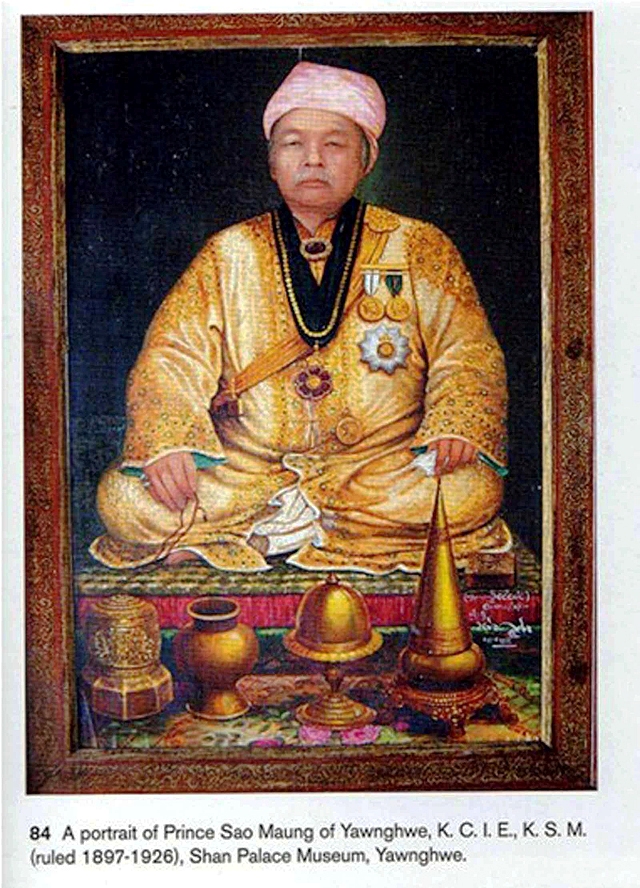

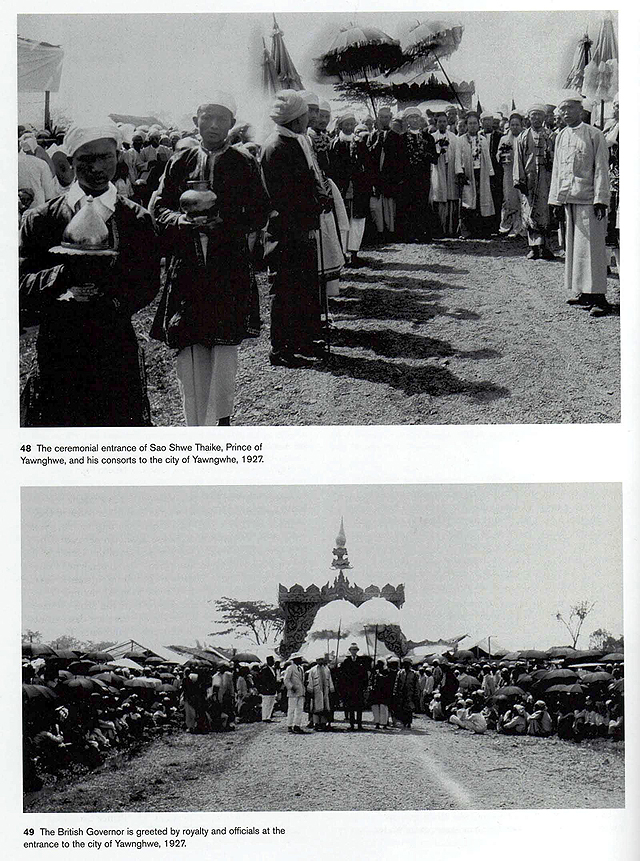

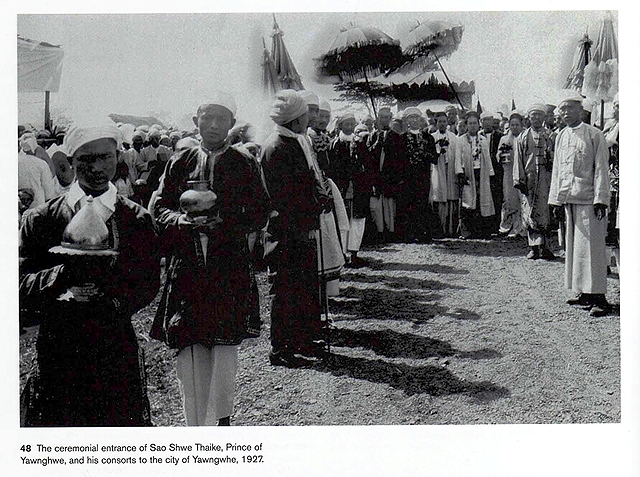

Shan States together with Burma proper, gained independence from British on January 4, 1948 and formed Union of Burma. The first President of Union of Burma was Sao Shwe Thaike, (q0fjolpfbwFufh) Shan SaoPha of YaungHwe.

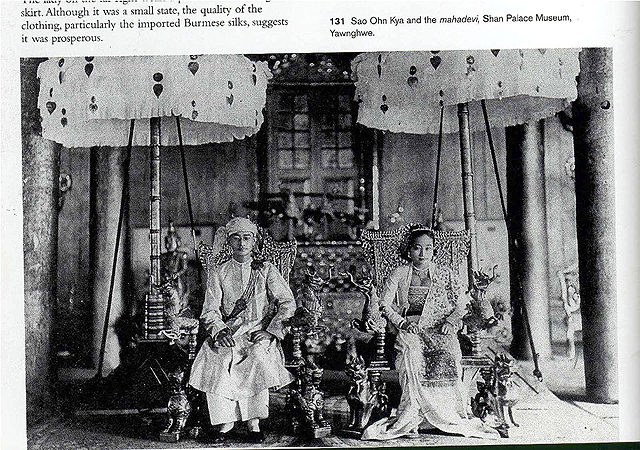

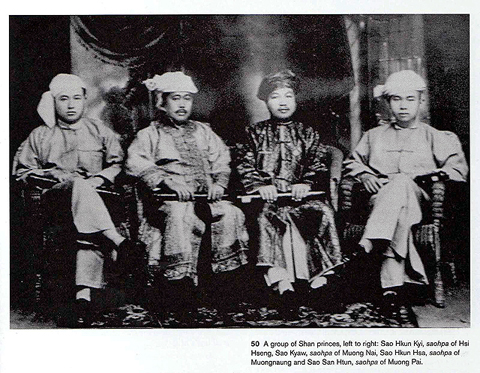

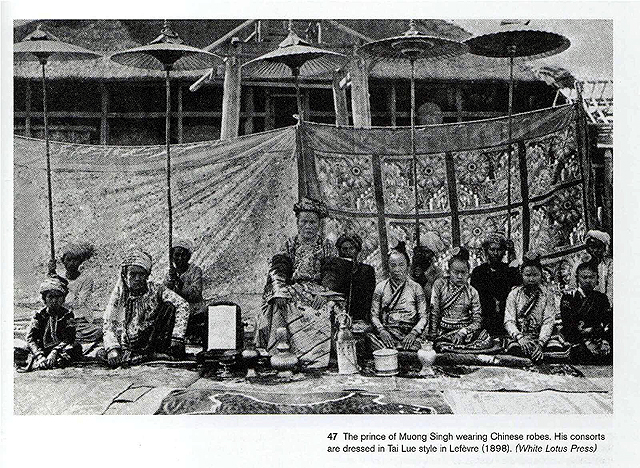

In the past, a Muong (မိူင်း) (Territory) was governed by a hereditary chief called “SaoPha” (ၸဝ်ႈၾ) literary means “Lord of the Sky.” The political and geographical situation of the Shan States changed in 1886 when Burma became a British colony. The Shan States, with other “Hill States,” were allowed to remain autonomous, which meant that in the Shan States the SaoPha would still rule over their States or Muongs. The British Government respected and recognized the authority of the Shan SaoPha. Small States were absorbed into bigger ones, old States dismantled, and new ones formed. A SaoPha’s salary depended on a fixed fraction of the State revenue. Thus, a SaoPha with a bigger and more prosperous State earned a salary higher than one with a smaller and less prosperous State. About thirty-five per cent of the revenue was contributed to the Central Government, and the rest was used for State Administration.

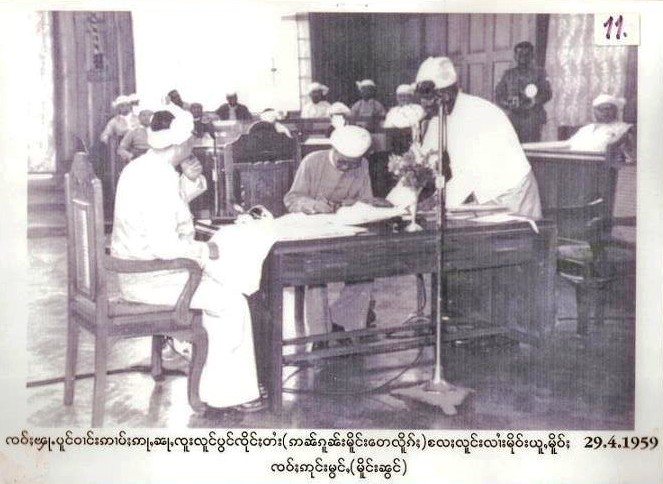

Before World War II, the Shan had been content to be ruled by the SaoPha. After the war SaoPha found themselves having to deal with activists in their own States, some were anti-SaoPha and others anti-British. The people’s demonstrations were putting pressure on the SaoPha to relinquish the power. In 1958 the SaoPha agreed to the demand of the temporary military government led by General Ne Win and relinquish their power and hereditary rights. No more ruling SaoPha since 1958.

Culture and Custom

Shan have their own language, literature, belief, dress, festivals and practices, which they proudly called “Shan culture.” However it is difficult to say whether it is an “Authentic Shan Culture” or “Buddhist Practices.” For instance, the novice ordination festival (ပွႆးသၢင်ႇလွင်း) normally held in March is, as claimed by the Shan, a Shan culture. It fact it is a Buddhist customs to make their sons becoming monks for a month in monastery to obtain merit for better future. Since Shan people have adopted Buddhism for almost two thousand years, all Buddhist practices have naturally and automatically become their culture. Buddhist festivals, activities and practices are sometime identified or assumed or considered or claimed as Shan culture.[23] Sometime they call it “Buddhist Shan Culture.” Shan people claim that Buddhism is Shan religion, Shan are Buddhists and Buddhism is Shan culture. People have been identified with religion. Thus it makes Shan very difficult to become Christian or belong to other religions.

The questions are:

- Is Buddhism Shan religion?

- Where does Buddhism come from?

- Is culture a religion?

- Is religion a culture?

- Is Buddhism Shan culture?

- Can religion become culture or part of the culture or foundation of culture?

- How can a Shan become Christian without abandoning their culture?

- How can a Shan continue participating in Shan cultural activities when he becomes a Christian, since their culture is Buddhist practices?

These questions are very important for the Shan, Shan Christians, and missionaries who work among the Shan. There are many Buddhist rites, which Shan have been adopting and practicing for centuries as their culture. They follow them and use them in their daily personal, social, and community life. They have a unique way of celebrating festivals, giving names to a child, courting and marriages, dedication of a new home, death and burial, etc., which Shan Christians call “Buddhist practices.”

Language

The Tai people in different countries and places still have many words in common, although changes in dialect and accents. There are common languages and terms among Tai, Thai, Lao, Shan, Dai, and Tai Ahom despite their separation for hundreds of years. For instance, they all call “rice” as “kao” (ၶဝ်ႈ), and the “spirit” as “Phe” (ၽီ), “water” as “namm” (ၼမ်ႉ)? The number, one (ၼိုင်ႈ), two (သွင်), three (သၢမ်), four (သီ), five ([ႁႃႈ), six (ႁူၵ်း), seven (ၸဵတ်း), eight (ပႅတ်ႇ), nine (ၵဝ်ႈ), ten (သိပ်း) are the same. They also have similar dress and the same method of cooking, dressing, lifestyle, and common food. Shan language belongs to the Tai linguistic group, which also includes the Thai, Lao, and Zhuang languages.[24]

The Shan language is different from other languages in Burma. In their language, the Shan call themselves Tai (တႆး) and their country Muong Tai (မိူင်းတႆး) and their language Tai language (ၵႂၢမ်းတႆး). The Tai languages are a subgroup of the Tai-Kadai language family.

Six Central Tai Languages

Southern Zhuang (China)

- Eastern Zhuang (China)

- Man Cao Lan (Vietnam)

- Nung (Vietnam)

- Tày (Tho) (Vietnam)

- Ts’ün-Lao (Vietnam)

One Northwestern Tai Language

- Turung (India)

Four Northern Tai Languages

- Northern Zhuang (China)

- Nhang (Vietnam)

- Bouyei (Buyi) (China)

- Tai Mène (Laos)

Thirty-two Southwestern Tai Languages

- Tai Ya (China)

- Tai Dam (Vietnam)

- Northern Thai (Lanna, Thai Yuan) (Thailand, Laos)

- Phuan (Thailand)

- Thai Song (Thailand)

- Thai (Thailand)

- Tai Hang Tong (Vietnam)

- Tai Dón (Vietnam)

- Tai Daeng (Vietnam)

- Tay Tac (Vietnam)

- Thu Lao (Vietnam)

- Lao (Laos)

- Nyaw (Thailand)

- Phu Thai (Thailand)

- Isan (Northeastern Thai) (Thailand, Laos)

- Ahom (India – extinct. Modern Assamese is Indo-European.)

- Aiton (India)

- Lü (Lue, Tai Lue) (China, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Myanmar)

- Khamti (India, Myanmar)

- Khün (Myanmar)

- Khamyang (India)

- Phake (India)

- Shan (Myanmar)

- Tai Nüa (China, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos)

- Pu Ko (Laos)

- Pa Di (China)

- Southern Thai (Pak Thai) (Thailand)

- Tai Thanh (Vietnam)

- Tày Sa Pa (Vietnam)

- Tai Long (Laos)

- Tai Hongjin (China)

- Yong (Thailand)

Other Tai Languages

Kuan (Laos)

Rien (Laos)

Tay Khang (Laos)

Tai Pao (Laos)

Tai Do (Vietnam)

Shan language is a tonal language and is written in a circular script called Shan script. Every variation in the voice and tone, such as low tone, high tone, medium tone, short tone, long tone, and intermediate tone, makes a difference in meaning. Altogether, there are six basic tones; some have three variations according to whether the mouth is wide open, closed, or partially closed. Apart from what Rev. J. N. Cushing calls opened, closed, and intermediate tones, there are eight distinct inflexions of the voice in pronouncing words in the Lao dialect, seven in the Khamti, and six in the Shan of Burma. The language, in all its known dialects, is rich and abounding in synonyms.

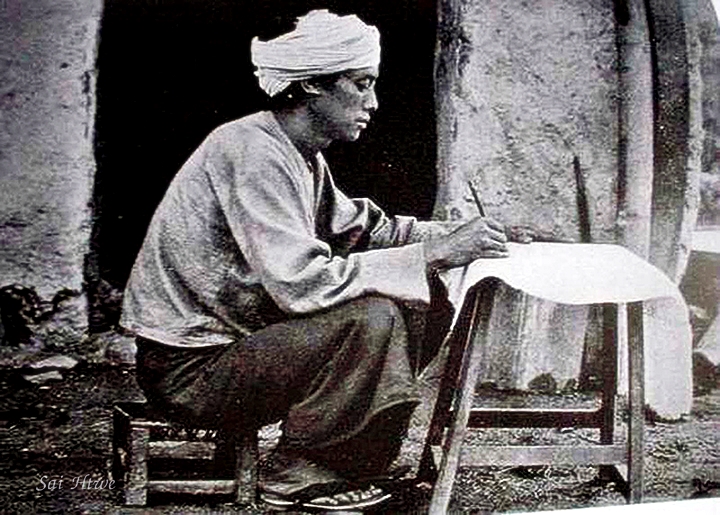

Literature

Shan has their literature. King AbiYaZa of DaKong (later renamed YanGon) (ရန်ကုန်) created the Shan script from Sanskrit in AD 483. In the beginning, there were 54 letters. The Tai Ahom in India are still using this script today. It’s called “Leik To Ngok.” (လိၵ်ႈထူဝ်ႇငွၵ်ႈ)

In AD 723-748 the King of Nan Chao said that the character was not beautiful and he changed it into more square character and also abandoned some letter that were not commonly used. Dai in China are still using this script today.

In AD 1283 the king of Sukotai (Thai), King Rama Kamhaeng, created new script by mixing up the round script which was created by King AbiYaZa and the square script which was created by King Nan Chao. It is still used in Thailand and Laos today.

In AD 1416, the King of HsenWi, Sao Kham Kai Hpa, changed the letter of Shan to another new rounded script. It is now called “Old Shan script” in Burma. Most of the Shan books were written with this script. The old writing system of the Shan has problems in reading, pronouncing, and understanding. One of the Shan Christian missionaries wrote the story of the prodigal son in Shan: “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before thee, and am no more worthy to be called thy son, make me as one of thy hired servants.” But the Shan boy read the story as, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before thee and am no more worthy to be called thy son, make me as one of thy baby elephants.” The words “hired servant” (လုၵ်ႈၸၢင်ႈ) and “baby elephant” (လုၵ်ႉၸၢင်ႉ) have the same writing in old Shan writing, but can be read in a different tone and have different meanings. It should be correctly read as “zann” (ၸၢင်ႈ) with normal and long tone instead of “zan” (ၸၢင်ႉ) with short and high tone. Another writing (ယႃသိၼ်ၼမ်ၶမ်တေဢဝ်သင်မွင်) “What to use to prick out the thorn?” the boy read; “Nun from NamKham will marry San Maung” (ယႃႊသဵၼ်ႈၼမ်ႉၶမ်းတေဢဝ်သင်မွင်ႇ). Because of the tone of the word, “thorn” becomes “Nun” and “what to use to prick out” becomes “will marry San Maung.” What a difference! The two words “wife” and “mother” are also written in the same word (မေ) in old writing. One has a high tone and the other has a normal tone. If one reads with the wrong tone, “wife” will become “mother,” or “mother” will become “wife.” Another example: the word (ၶႃ) (Ka) can give seven meanings, such as leg (ၶႃ), or frame suspended over fireplace (ၶႃ), or slave (ၶႃႈ), or thatch (ၶႃး), or gossip (ၶႃႉ), or branch of a tree (ၶႃႊ), depending on the tone. More interestingly the word “kein” (ၶိင်) can give ten different meaning, depend on the tone make on reading the word, such as; Ginger plant (ၶိင်), Time (ၶိင်ႇ), Mr (ၶိင်း), Chopping block (ၶဵင်), Shelf (ၶဵင်ႇ), Stretch out (ၶဵင်ႈ), Tough (ၶႅင်), Tax (ၶႅင်ႇ), Small dried pieces of bamboo (ၶႅင်ႈ), Woven map for drying (ၶႅင်း). Since there are no tone marks and special characters in old Shan script, the reader can misread, mispronounce, and get the wrong meaning. The Shan Bible was translated and written by Rev. J.N. Cushing in 1892 with this old writing system.

In 1940, Sao Hsai Muong and the Shan literary committee created a new Shan script and writing system by adding some tone marks and new characters to make the letters more accurate in writing and reading. It is now called “New Shan Script.” The old writing system was used in Shan literature for more than four hundred years until the new writing system was fully developed in 1958. Shan-English and English-Shan dictionaries were produced by Rev. J. N. Cushing in 1881 and revised by H.W. Mix in January 1914. A revised version of Cushing’s Shan-English dictionary in new Shan script was done by Sao Tern Moeng and published in 1995. The Shan dictionary was written by Gant Kham Sung Sum and published in December 2001.

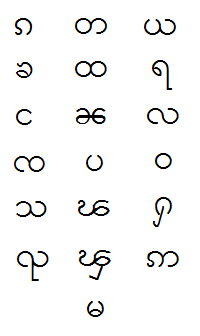

(Sample Of Old Shan Writing)

ၼင်ႁိုဝ် ၶဝ်ၸိုဝ်ဢၼ်ယုမ်မတ်လုၵ်ၽြႃပဵၼ်ၸဝ်တင်သိင်တင်လူင်ၼၼ်တၵ်ဢမ်လႆႁွတ်ထိုင်တင်လုတင်လိဝ်လေတၵ်လႈဢသၵ်ထႃဝရႃၸိုင် ၽြႃပိၼ်ၸဝ် ႁၵ်ၵူၼ်လေႃၵီတင်လႆ တေႇထိုင်ႁွတ်ထၼ်ပေႃၸုၼ်ပိတ်လုၵ်ၸဝ်ပႃလိဝ်ဢၼ်မီတီမၼ်ၸဝ်ၼၼ်ဢေႃ။

(Sample Of New Shan Writing)

ၼင်ႇႁိုဝ် ၶဝ်ၸိူဝ်းဢၼ်ယုမ်ႇမၢတ်ႈလုၵ်ႈၽြႃးပဵၼ်ၸဝ်ႈတင်းသဵင်ႈတင်းလူင်ၼၼ်ႉ တၵ်းဢမ်ႇလႆႈႁွတ်ႈထိုင်တၢင်းလူႉတၢင်းလႅဝ်လႄႈ တၵ်းလႆႈဢသၢၵ်ႈထႃႇဝရႃႉၸိုင် ၽြႃးပဵၼ်ၸဝ်ႈ ႁၵ်ႉၵူၼ်းလေႃးၵီႇတင်းလၢႆတေႃႇထိုင်ႁွတ်ႈထၼ်ႈပေႃးၸုၼ်ႉ ပႅတ်ႈလုၵ်ႈၸဝ်ႈပႃးလဵဝ်ဢၼ်မီးတီႈမၼ်းၸဝ်ႈၼၼ်ႉဢေႃႈ။

There are 18 alphabets in the old writing system and 20 in the new Shan writing system. Some use two more alphabets in the new system. There are 20 initial consonants, 10 plain vowels, 12 diphthongs, and 6 tone marks in the new Shan writing system.

Regretfully Shan literatures are not allowed to be taught in public schools in Shan States. All public schools are government schools. Nowadays younger generation prefer reading Burmese instead of Shan because of the following reasons.

They do not have a chance of learning Shan at school.

They learn Burmese at school and know only Burmese well.

They know Burmese better than Shan.

There are very few books written in Shan.

Very few educational books or interesting books are written in Shan.

No educational books such as science, medicine, engineering, arts, agriculture, and mining are written or translated in Shan.

ၵ ၶ င ၸ သ ၺ တ ၻ ႀ ထ ၼ ပ ၿ ၽ ၾ မ ယ ရ လ ဝ ႁ ဢ

Twenty Shan alphabets in new system

Shan Calendar and New Year

The Shan have their own calendar since ancient days started in AD 638. There are books in Tai script for calculating solar and lunar eclipses.

First Waxing Moon of the First Lunar Month, Lern Seign (လိူၼ်ၸဵင်မႂ်ႇဝၼ်းၼိုင်ႈ) is considered Shan New Year Day according to the Shan Calendar. There are three supposed reasons for the existence of the Shan New Year.

- The Shan Kingdom of Muong Mao was founded in 450 Buddhist Era (BE).

- The Abbot of Man Hai, SeLan, had written that in the year 450 BE there was the assembly of 150 learned Buddhist monks where they re-wrote the three divisions of Buddha’s doctrine (i.e. the Buddhist Synod).

- Sao Khun Sai @ Sao Khun Hong, the son of the King of Muong T’sen (modern Yunnan) (မိူင်းသႅၼ်) with his four followers went to fetch the Buddha’s doctrine in the land of Phar Tang Phar Taw and returned home in the 450 BE in the time of new harvest.

That is why Shan calendar year (ပီႊတႆး) is based on the 450 BE.

The Shan year is equal to Buddhist calendar year (Burmese year) minus 450 years.

For example, 2545 (Buddhist year) – 450 = 2095 (Shan year) = AD 2001

Festivals

Shan are festival loving people. For the Shan life is meaningless without festival. There are festivals all year round in Shan States. Traditional ceremonies take place throughout the year. Most of these festivals are related to Buddhist calendar and very similar to Burman’s festivals.

Mid December – Mid January ( လိူၼ်ၸဵင် )

Shan New Year day (လိူၼ်ၸဵင်မႂ်ႇဝၼ်းၼိုင်ႈ) celebration in early December.

Moe-Byae Festival. Full-moon day of Pyatho (Moe-byae, Shan State), 3-day festival ending January 1. The traditional crossbow contest is the main highlight of this festival.

During cold winter months, after the rice has all been harvested from the field, people make stuffing-cooking rice (khao lam mok) (ၶဝ်ႈလၢမ်မွၵ်) inside bamboo sticks and cook it by putting it under burning charcoals. People also make sticky rice cake (khao boak) (ၶဝ်ႈပုၵ်). If it is mixed with sesame seeds, it is called Khao Tam Nga (ၶဝ်ႈတမ်ငႃး).

Mid January – Mid February ( လိူၼ်ၵမ် )

The people celebrate the tradition of Khao Ya Goo (ၶဝ်ႈယႃႇၵု) by giving out red sticky rice parcels. They make it with steaming sticky rice and mixing it with sugar cane, coconut and peanuts. They take the rice cakes to the temple to make offerings and also give them out to their friends and neighbors.

Mid February – Mid March ( လိူၼ်သၢမ် )

Baw-gyo Festival. 10th waxing day of Tabaung (Hsibaw, Shan State), 5-day ceremony ending Mar 1. There are boat races on the Dote-hta-wa-di River.

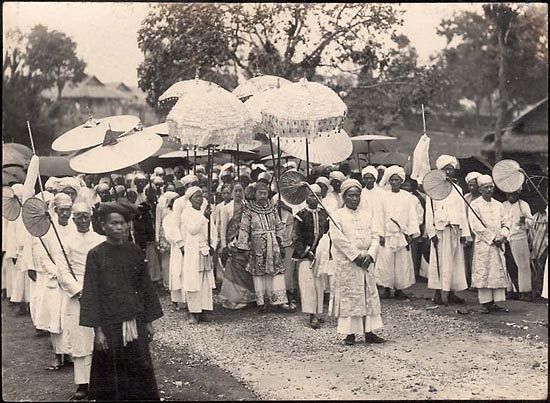

Monkhood festival or novitation ceremony (Poi Sang Long) (ပွႆးသၢင်ႇလွင်း), which is the ordination of young Shan boys as novices.

Mid March – Mid April ( လိူၼ်သီႇ )

Pindaya Cave Pagoda Festival. 11th waxing day of Tabaung (Pindaya, Shan State)

5-day ceremony ending March 19. This is a typical Taungyo pagoda festival where different ethnic minorities can be seen celebrating in their colorful garb.

Pindaya Shwe Oo Min Pagoda Festival (Pindaya, Shan State) in Pindaya, about 45 km North of Kalaw, around the full moon day of Tabaung. During the festival time, thousands of devotees throng to the cave to pay homage.

The water-splashing festival (Swan Nam) (ပွႆးသွၼ်းၼမ်ႉ), during which time the people splashing water to one another and to the Buddha statue, prepare sticky rice food wrapped in banana leaves (ၶဝ်ႈတူမ်ႈၵူၺ်ႈ) and make offerings to earn merit for the Buddhist New Year. Shan people claim this festival as Shan culture, but Shan Christians in Burma see it as a Buddhist festival and do not allow its members to join the festival.

Mid April – Mid May ( လိူၼ်ႁႃႈ )

Watering the Sacred Bo Tree Festival or Kason Festival held on the Kasone full moon day on the Buddhist calendar, the event marks the commemoration of the Buddha’s birthday by pouring water onto the scared Bo tree, under which Guadama attained enlightenment and became the Buddha.

Taung-yo Torchlight Procession Festival in Pindaya, Shan State.

The festival of Sand Pagoda (Poi Kong Mu) ( ပွႆးၵွင်းမူးသၢႆး) takes place during which time the people collect sand and take it to the temples to make little Kong Mu (pagoda) in the temple grounds during the time of the full moon and they all join together to make merit.

Mid May – Mid June ( လိူၼ်ႁူၵ်း )

The people make offerings to the village spirits at various sites throughout the area.

Mid June – Mid July – ( လိူၼ်ၸဵတ်း )

Nayone Festival of Tipitaka.

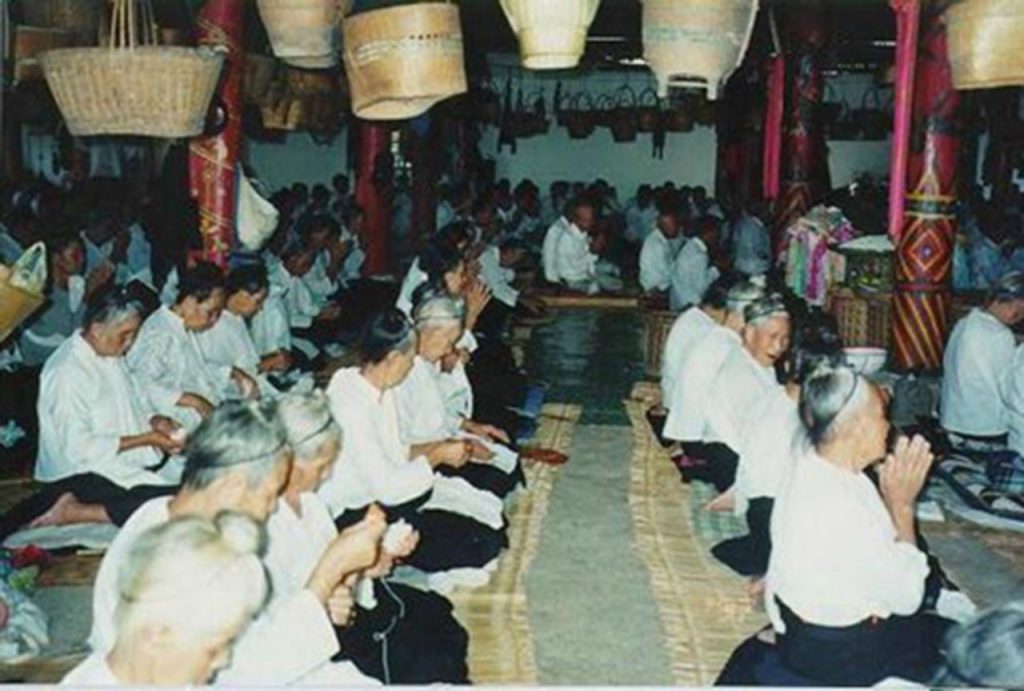

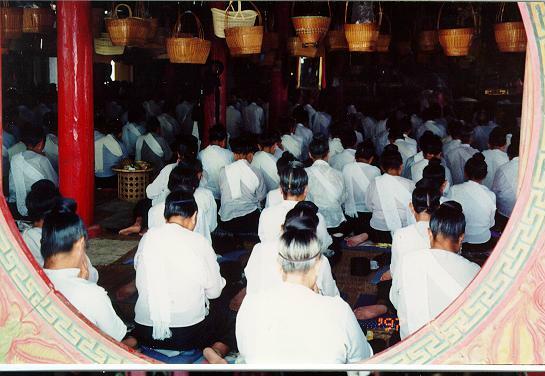

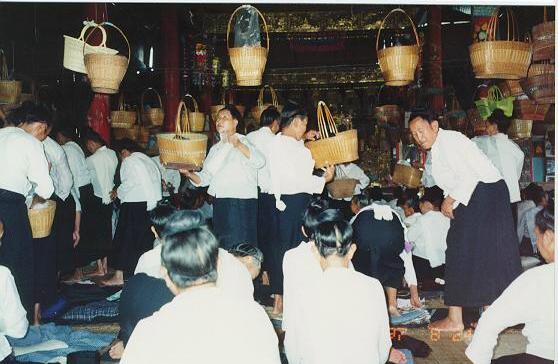

The festival of offering alms (Poi Kap Som) ( ပွႆးၵပ်းသွမ်း ) is held to make offerings of specially prepared food to the older people who are spending the Buddhist Lent months in the temples.

Mid July – Mid August ( လိူၼ်ပႅတ်ႇ )

Dhama Sakya Day. This day commemorates the Buddha’s first sermon to his five disciples.

The Waso Festival, commemorating the Buddha’s first sermon, this festival also marks the beginning of Buddhist Lent. Monks are given new robes and other requirements to tide them through the months ahead.

Mid August – Mid September ( လိူၼ်ၵဝ်ႈ )

The Phaung Daw Oo Festival and the Thadingyut Festival of light are held for 3 weeks during September/October. It is the biggest event in the Shan States. It is also a celebration to mark the end of the Lent season. In the evening, people make processions carrying handmade castle-like structures to the temples or else place them outside their homes to bring merit to their families. During these ceremonies, there is music and dancing. The dancing is done by dancers dressed up as mythological creatures such as the mythological half-bird-half-human (ginaree) ( ၼူၵ်ႉ ) and the mythological yak ( တူဝ်း ), which is held by two dancers, rather like a pantomime horse.

Mid September – Mid October ( လိူၼ်သိပ်း )

The festival of Hen Som Go Ja ( ႁၢင်ႈသွမ်းၵေႃးၸႃႇ ) ( ပွႆးၶဝ်ႈဝႃႇသႃႇ / ပွႆးဢွၵ်ႇဝႃႇ ) is celebrated to commemorate the welcoming of the Buddha coming back from heaven, where he went to visit his mother during the Lent season. It is held to make offerings to deceased relatives who have already passed away.

Mid October – Mid November ( လိူၼ်သိပ်းဢဵတ်း )

InLe Festival. 1st waxing day of Thadingyut (Inlay, Shan State) 18-day festival. Four Buddha statues are ceremoniously tugged clockwise around the lake on the royal barge by leg-rowing boats. They return home on the 3rd waning day. Leg-rowing boat races are held throughout the event.

Mid November – Mid December ( လိူၼ်သိပ်းသွင် )

Tazaungdaing (Tazaungdine) Festival is held over 3 days in mid-November and is another festival of light. A spectacular fire-balloon competition is held in conjunction with the festival. These huge balloons are made of local Shan paper or rags, and are of different sizes and shapes, some human, some animal, some just fanciful products of imagination.

Hospitality

Shan are very hospitable people. They always open the doors of their home to visitors, passersby, or strangers. Even though they have never met or known each other before, they offer a place to rest or stay for a night or two or even for a week. They believe that taking care of the guest is a good deed and can earn great merit. At least the visitors or strangers are offered a cup of cold water or hot green tea when they come into the house. A stranger who has happened to be at home at mealtime is always invited to the table. When a stranger comes after mealtime, the visitor is always asked if he has had his meal. If not yet, the host usually prepares a meal for the visitor.

Leslie Milne said, “A poor Buddhist nun whom I thus treated, she was so grateful that for days she supplied me and my servants with vegetables and fruit. Her gratitude also taking embarrassing form of coming to say her prayers – presumably for me – in my bed room when I was dressing.”

A small bamboo stand on the side of the road covered with a tiny thatched roof, shading a water pot, is a common scene in Shan village. Women and girls used to fill the water pots with water every day. The water is freely available for passersby. They have been taught that a cup of cold water given to tired and thirsty wayfarers brings much reward in the future life.

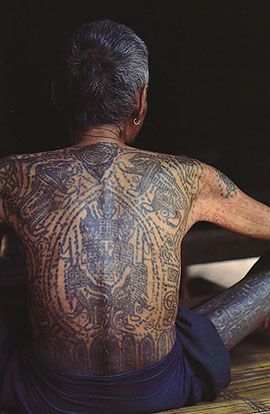

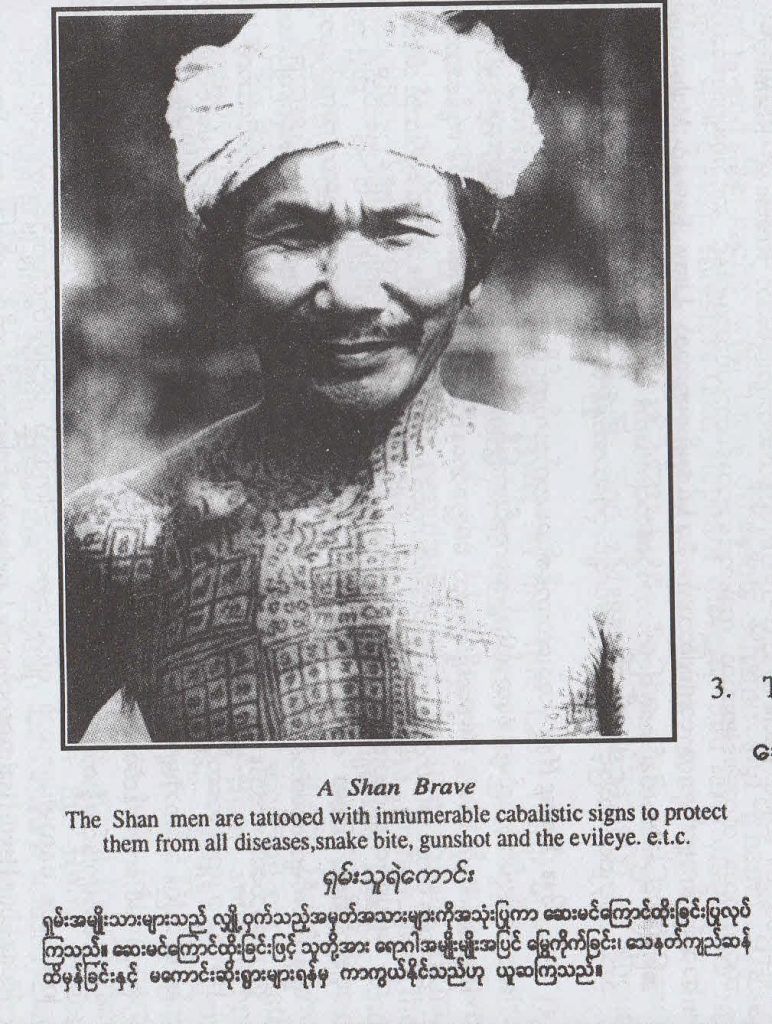

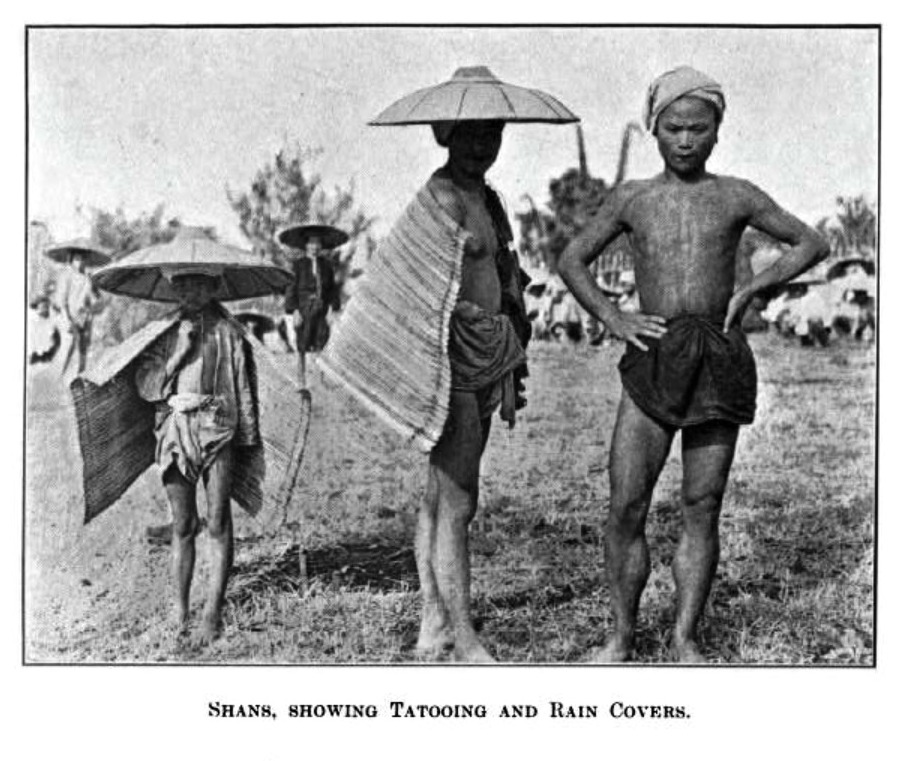

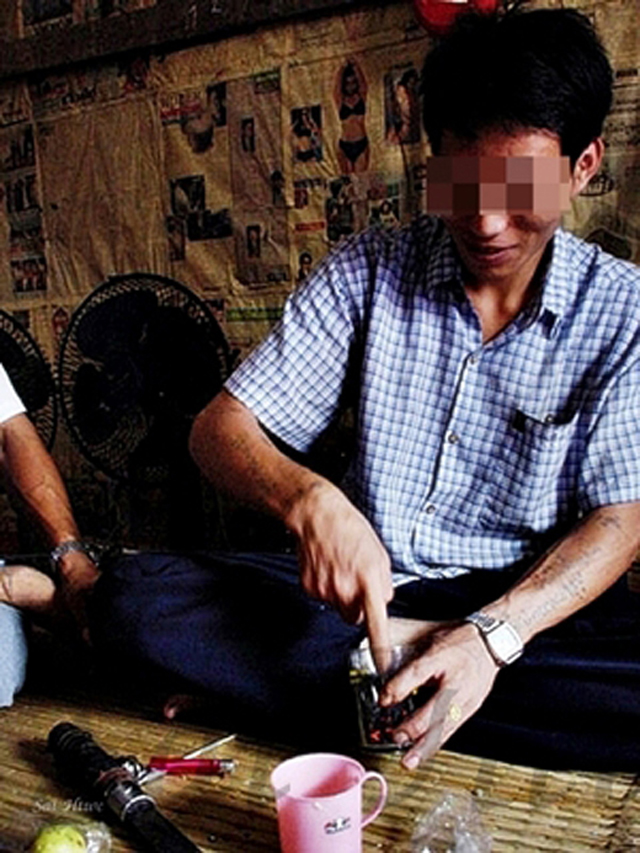

Tattooing

Tattooing properly had been practiced in most parts of the world, though it was rare among populations with dark skin color and absent from most of China (at least in recent centuries). Various people believed that tattooed designs could provide magical charm, protection against sickness or misfortune. Some considered tattooing could make people have power, free from evil and danger. Some might even think as a beauty. Some tattoos were useful as an identity of a person’s race, rank, status, or membership in a group. Tattoos had also been found on Egyptian and Nubian mummies dating from about 2000 BC. After the advent of Christianity, tattooing was forbidden in Europe, but it persisted in the Middle East and other parts of the world.

In the past, all males had to have tattoos. Without a tattoo, he was not considered a mature or brave man but was considered immature and a coward. Women did not like a man who had no tattoos. There was a saying, “Yellow leg, get back away from our fields, otherwise our spirit of the field will flee.” In those days, a man with no tattoos could hardly find a wife. Some tattooed from neck to ankle, covering the whole body. Some only had tattoos on their arms and a small tattoo on the chest and back. The tattooing instrument is a single split needle set in a heavy brass socket or a few needles tightly tied together. No ink but the bile from the gall of a bear was used in tattooing the skin. Women seldom tattooed unless they were crossed in love.[27] Tattooing is still practiced now, but many young generations have abandoned it.

Sickness and Medicine

In the old days, traditionally, Shan believed that there were ninety-six diseases affecting the body of human body. Shan used to blame Phe (spirit) (ၽီ) for their sickness and disease. Shan used many herbs as medicines in treating diseases extensively for hundreds of years since they used to lived in the forest, hills, and jungle without knowledge of western medicine. They used to go into the jungle, the field, and find the medicinal leaves and roots for treating ailments. Sometimes they spend days in the jungle to find herbs. They had many formulas for making herbal medicine. Some of the animal parts and bones were also used as medicines. They knew how to distinguish between edible food and poisonous food. They sometimes made use of poisonous food to create poison for catching wild animals.

Sometimes the barks of certain trees were boiled and given to the sick as a remedy for certain diseases. Sometimes bark was pounded between stones, and dry powder was used to sprinkle on wounds for healing. Sores and wounds were sometimes bathed with kerosene oil and alcohol. Shan recognized the fact that some diseases might be contagious or infectious, and they burned the clothes of any person who had died of such a disease. If a serious epidemic occurs in a village, the sick are often left to the care of a few old people, and the other inhabitants leave their homes and build huts for themselves in the jungle and live there until they think the danger is over. If the epidemic had been very severe, many people died in the village, people deserted their village, and rebuilt a new village on a new site. Epidemics were sometimes thought to be caused by certain bad spirits. Offerings were placed for those bad spirits at the roadside to feed them and appease them not strike the village. A pole with a swivel attached was also erected close to a path so that the demon might be caught as it passed by.

Massage was a general relief and cure for all complaints, and it was often done with the feet on the back and thigh and with the hands on the neck and arms. For snakebite, a string was tightly tied above the wound. After some one had sucked the poison out from the wound, a paste made of pounded spiders was laid upon the bite. They believed it counteracted the poison. Opium was commonly used as a local application to relieve pain. The flesh of bats was considered good for asthma, but it must be thoroughly cooked. Bones of tigers ground into powder were given as a tonic to anyone recovering from a severe illness to restore strength. The claws of a bear were used as charms against sickness. Scraping on the leg or arm with the tusk of a wild boar was considered a cure for stiffness or rheumatism of joints. The claws of a tiger or leopard were in great demand for charms to make children brave. The powdered horn of a rhinoceros was one of the most expensive remedies for all diseases. Tiger flesh dried in the sun, powdered, and eaten by small children could prevent them from having fits or convulsions. Tiger’s bones soup was good for dropsy, beriberi, and other swelling diseases. Shan also used Western and Chinese medicines whenever available.

Some believed that the seat of life changes its position from day to day. It might be in the hand today, and tomorrow in the head, and the next day in the arm. That was very serious if someone happened to cut their foot when the seat of life was visiting the foot. He was most certain to die. Some healers used to ask the time and date of birth of the sufferer before giving treatment because some treatment depends on the day and the time of the birth of the patient. Shan, in the past, did not know about surgery. A favorite practice, when all other remedies failed to bring relief, was to puncture the skin of the patient with a hot needle to let out the blood, and the evil spirit would leave. It is easy to win the confidence of the people if one knows something about medicine and can help people with illnesses. [28]

Making Covenant ၵိၼ်ၼမ်ႉသႅတ်ႉၸႃႇ

In the old days, keeping promises was a very serious matter for Shan people. Agreements were sometimes sealed curiously. One custom of keeping or making a promise was “drinking water of faithfulness.” The promise was repeated verbally over water, which was stirred with a dagger or the point of a sword, and the water was then drunk, half by one man and half by the other, both calling on heaven and earth to witness the agreement. Another way was by writing an agreement, and then burning it, and the ashes were sprinkled on water, and each man swallowed half, saying before he drinks, “May I become very ill or die in a violent death if I do not hold good this writing.” A common oath was, “May I become a beast in my next life”[29]. They used to swear to the sky or the pit when making a verbal promise.

Cultivation and Farming

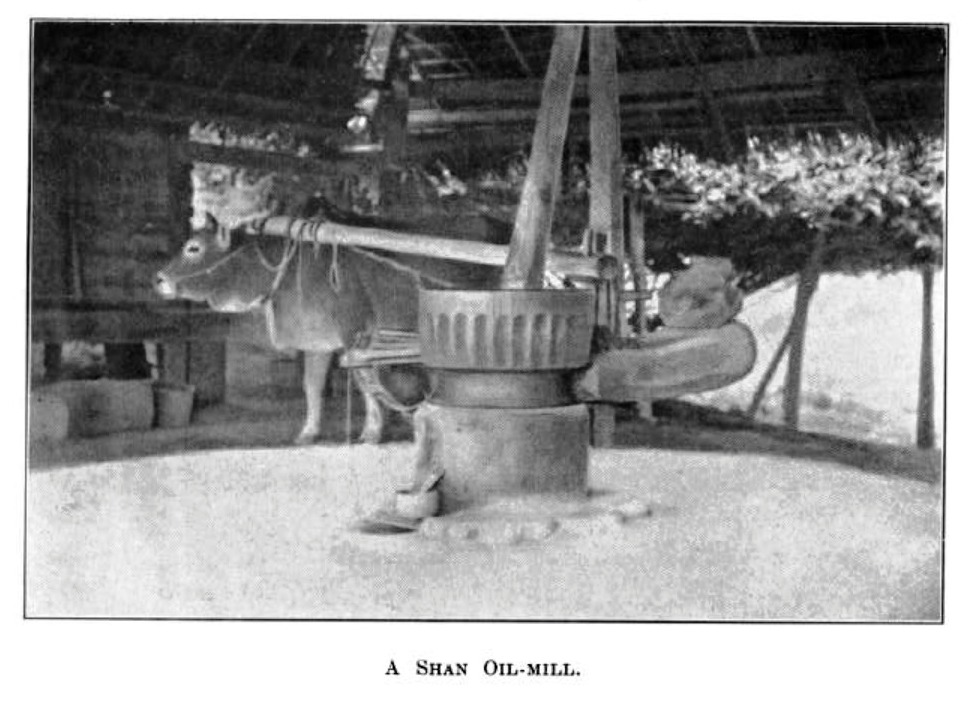

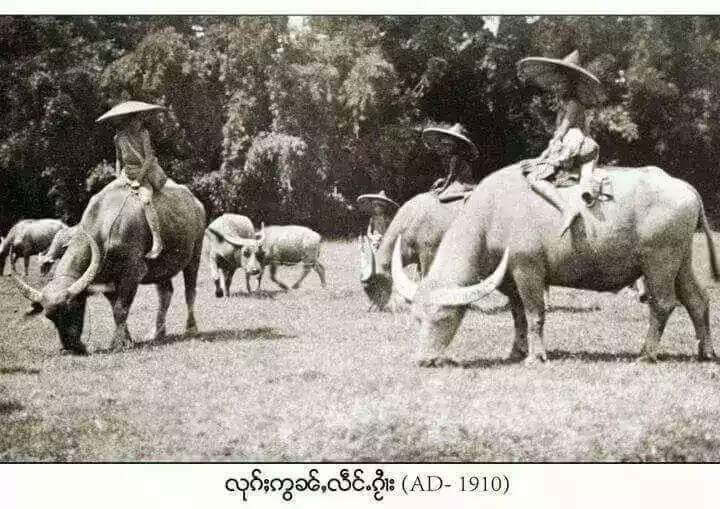

Shan people like living on high plateaus and places where there is plenty of water. Farming was their main occupation. Rice was the staple food. Shan used buffalo in ploughing the rice field and used cows in pulling the cart. Before starting farming, a stone of the spirit was placed in the middle of the field until harvest time. After harvest, a small portion of the crops was offered to the stone, and then the stone was brought back home. In the old days, rice grown by the family was for family consumption only. However, nowadays farmers are making money by selling rice from their fields. They kept enough rice for their family for the whole year before another harvest. Apart from growing rice, Shan also grew vegetables and fruits.

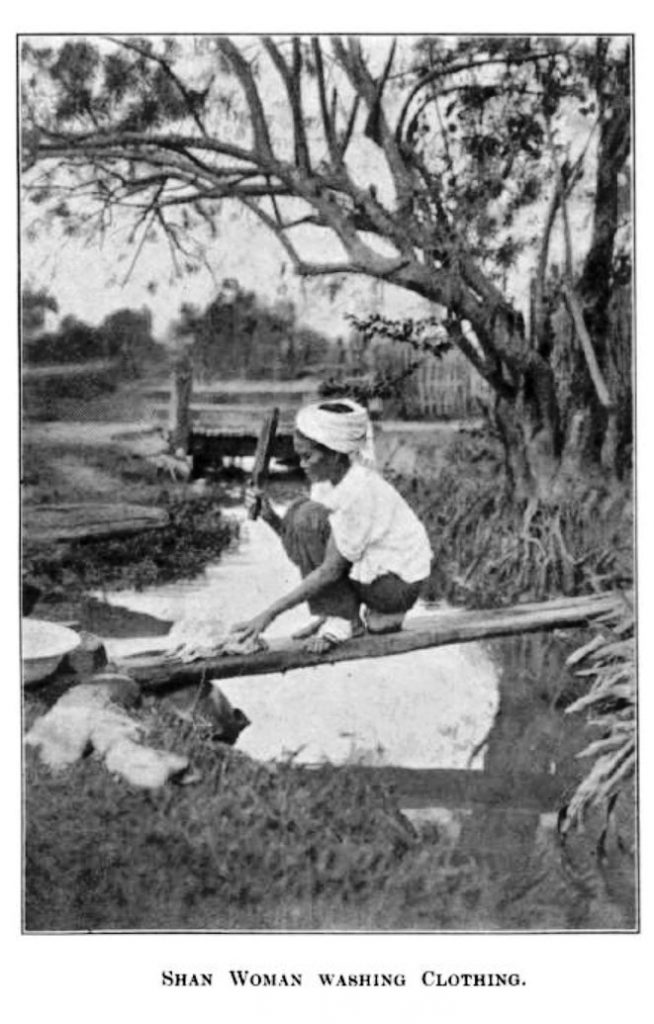

Life began early in Shan village. The women rose at cockcrow early morning before dawn to prepare the rice for the morning meal. The thud, thud, thud sound of pounding paddy in the kitchen about five o’clock in the morning was just like a sound that makes a wonderful alarm clock for the whole village. The men rose a little later. They ate breakfast, took tools, and departed from the house for the whole day’s work in the field or jungle and returned home at sunset. They paddocked the buffaloes or cows they had tended the whole day in the lower ground of the house, took bath, ate their evening meal, and retired to bed or puffing tobacco and drinking a cup of green tea or alcohol, talking and chatting round the flickering fire for a while before going to bed. They used to talk about the buffalo, cows, or water in the field. Economic or political factors were not common. They cooked late and ate late in the evening. Usually, dinner time started at 9 PM and finished at 10 PM.

Method of Farming

The Tai people group was the first in history to plant rice and use a furrow to plough.[30] The seeds of rice are first of all soaked in water until they sprout and then sown in small nurseries previously prepared by ploughing. At the end of thirty days, they were pulled out from the soil with the root attached and transplanted into the field, which was previously ploughed and filled with water. The seedlings were set one foot apart in straight lines. It’s back-aching work to bend down and plant the plants all day long in the field, but impromptu folk songs sung by planters helped them pass the time and pain. Sometimes it became an enjoyable moment.

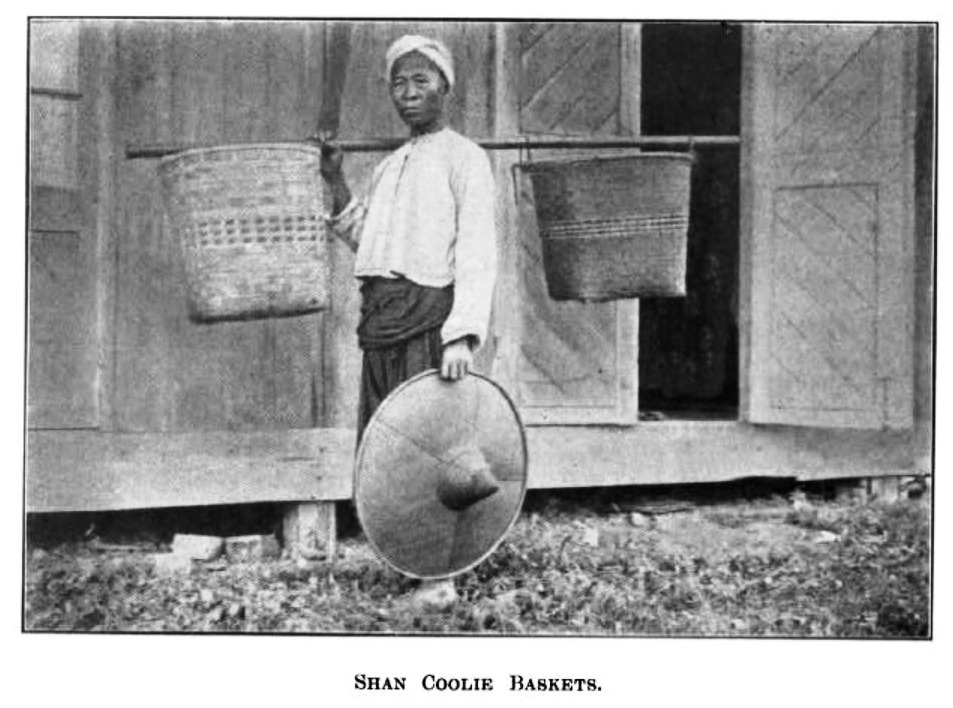

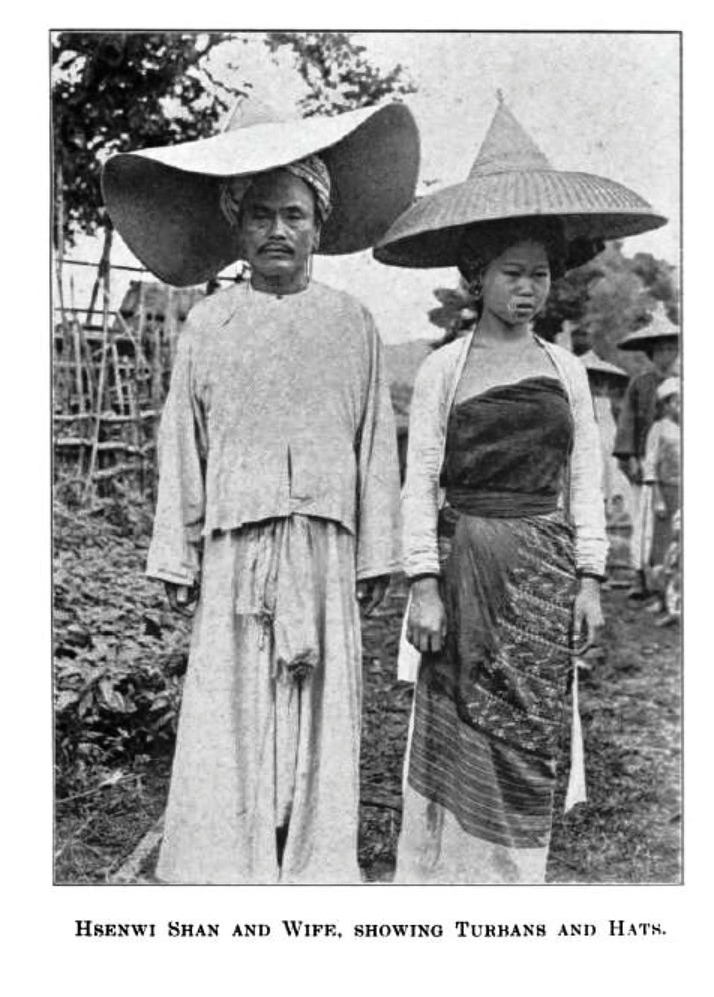

Both men and women helped in planting. They worked all morning till sunset with a short break for a meal during the day. They wore big hats usually made of bamboo cover, which was tied tightly under their chin to prevent it from falling off their heads. The big hat acted as an umbrella and protected their head and body from the sun and rain. Some covered their back with a coat made of leaves to protect themselves from the rain. They did not stop working even though it was raining. They wrapped their lunch from home in a banana leaf and brought it to the field. They ate a cold meal without reheating. Planting time usually ended in July. In November, the waving grains turned golden as it was ripe and ready for harvest. The most enjoyable time was harvest time. The reaping began in November or even as late as December. The grains were cut by sickle, and the swathes were tied together to make sheaves. The sheaves were then heaped up to make the large stacks. After reaping was over, the sheaves were left in stacks for two or three weeks before threshing. Threshing was usually done by hand, but if there was a large quantity, it was thrashed by buffaloes by stamping round and round through the paddy as it lay in heaps on the threshing floor covered with a bamboo mat. After thrashing the oxen carried the grain from the field to the village in large baskets, two baskets on each ox. Paddy was stored in big bamboo baskets, which were seven or eight feet high, tightly plastered inside and outside with clay to prevent insects and rats. The rice of the first ears that were threshed was cooked by steaming and carried to the monastery, and offered to the monks as an offering.

Empty rice fields after harvest were used again for planting either sugarcane or paddy. Shan also cultivate various spices and seasonings such as onions, garlic, lemon grass, white and black pepper, fennel, basil, chilies, coriander, horseradish, roselle, parsley and mint. Shan also raise pigs, cattle, poultry, ducks and elephants. Hunting is another traditional activity for the Shan with crossbows, snares, bamboo traps, stone slings or gun.

Handicrafts

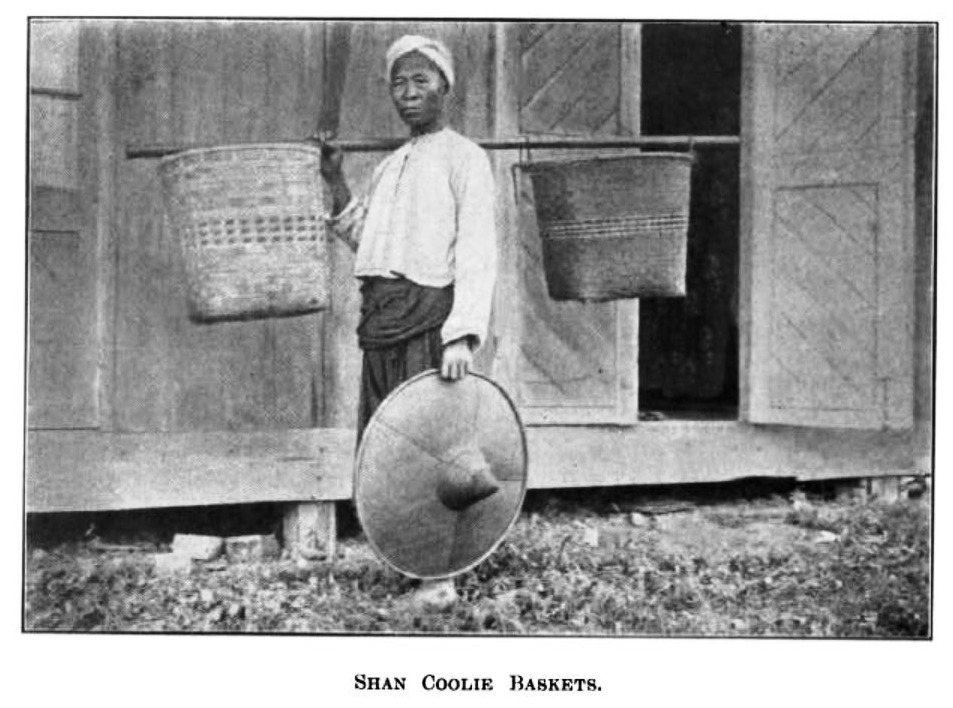

Shan are skillful in handicrafts, especially in gold, silver, metal, ivory, and weaving. With migration moving southwards to their present locations in Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, they added some forms of Khmer and Indian influence to their traditional inventory. Therefore, Tai textiles fall into two groups: original and supplemental textiles. The former grouping includes clothing, decorative, religious, and utilitarian textiles. Besides skill in silk weaving, Tai are also excellent basket weavers using strings of bamboo. A wide range of containers, baskets, and traps of different sizes for different purposes is produced. [31]

Food

The main food of Shan is rice. Shan people like sticky rice and all kind of cakes made of sticky rice. There are many verity of sticky rice cake such as Kao Boak (ၶဝ်ႈပုၵ်), Kao Kep (ၶဝ်ႈၶႅပ်ႉ), Kao Bong (ၶဝ်ႈပွင်း), Kao Lum Mok (ၶဝ်ႈလမ်မွၵ်), Kao Dum Kiou (ၶဝ်ႈတူမ်ႈၵူၺ်ႈ), Kao Soi (ၶဝ်ႈသွႆး), Kao Sian (ၶဝ်ႈသဵၼ်ႈ), Kao Muong (ၶဝ်ႈမူင်ႈ), Kao Moon Ho (ၶဝ်ႈမူၼ်းႁူဝ်ႇ) Kao Dum (ၶဝ်ႈတူမ်ႈ) etc.

Other favorite foods for Shan are; Toa Noa (Soya bean) (ထူဝ်ႇၼဝ်ႈ), Toa Fu Phet (spicy Toa Fu) (ထူဝ်ၽူးၽဵတ်), Phak Soum (Pickled leaves) (ၽၵ်သူမ်ႈ), Phak Kat Saw (stew mustard leaves) (ၽၵ်ၵၢတ်ႇၸေႃး), Lo (Bamboo shoot) (လူဝ်ႇ), Phak Keng (boiled leaves) (ၽၵ်ၵႅင်ႈ), Phak Kam (pea plant) (ၽၵ်ၶၢမ်း), Bak (Pumkin) (ပၵ်ႉ), Dean (Cucumber) (တႅင်ႈ) Pa Heng (Dry fish) (ပႃႈႁႅင်ႈ), Noua Heng (Dry beaf) (ၼိူဝ်ႈႁႅင်ႈ), Mixed vegetable (သႃႈ), Eatable tree leaves (ႁွတ်ႈ), Nam Pit (Pounded eggplant in chili pepper) (ၼမ်ႉၽိတ်ႉ), Noe Sa (meat-salad) (ၼိူဝ်ႈသႃႈ), Pa Soum (sour-fish) (ပႃႈသူမ်ႈ) kong Soum (Sour prawn) (ၵုင်ႈသူမ်ႈ), Noe Soum (Sour meat) (ၼိူဝ်ႈသူမ်ႈ), Pa Zi (BBQ fish) (ပႃႈၸီႇ), Noe Zi (BBQ meat) (ၼိူဝ်ႉၸီႇ), Pa Moke (Baked fish) (ပႃႈမူၵ်), Bamboo-worm (မူင်ႈမႆႉ) and other eatable larva are also Shan favorite food. Shan do not like oily food. Shan like drinking tea (green-tea). All visitors were offered green tea at any occasion. Drinking alcohol is not a Shan culture but they use to drink during eating meal, at festival and celebration. Sour and spicy foods are also Shan favorite.

Elderly Shan, male and female alike, were fond of chewing betel leaves. The reason for chewing betel leaves was that they believed betel leaves could make a person speak well, weightily, respectfully, and effectively. Before chewing it, they had to break away both ends of the betel leaf because they believed that there was a spirit watching over the betel leaf.

Cooking

Tai have a typical common methods in cooking such as;

Cook with boiling water in an open pot (ၵႅင်ႊ/ၸေႃး)

Cook meat or vegetables in a covered big pot ( ဢုပ်ႉ )

Cook meat or vegetables in a covered small pot (ဢွပ်ႉ)

Mixed salad with any condiment by chopping up uncooked food and mixing it with meat as the main ingredient (ၵူဝ်ႈလႄႈသႃႈ)

Cooked by baking under the hot charcoal or ashes (မူၵ်း/ဢွပ်း/ဢႅပ်း)

Cook in a bamboo pot over the fire. (လၢမ်)

Cooked by steam (လိူင်ႈ)

Prepared dishes by pounding (တမ်/ၼွၵ်း/ၶိူၵ်း)

Prepared by keeping it sour or fermented (မွင်ႊ/ယႅၼ်ႊ)

Roasted on the fire or barbecued (ၸီႇ/ပိင်ႈ)

Cook without anything added (တူမ်ႈ/ႁူင်)

Cooked by frying (ၶူဝ်ႈ/သၢဝ်း)

Stew food, cook slowly and long on medium heat, simmer (ဢွင်ႇ)

Soaked in liquid and eat (ၸႄႈ)

Dip in liquid and eat (ၸမ်ႈ)

Mixed, knead together with any condiment, commonly with sour vinegar, and eat(လူႈ)

Keep in cold condition and allow it to become solid or coagulated and eat (တုင်)

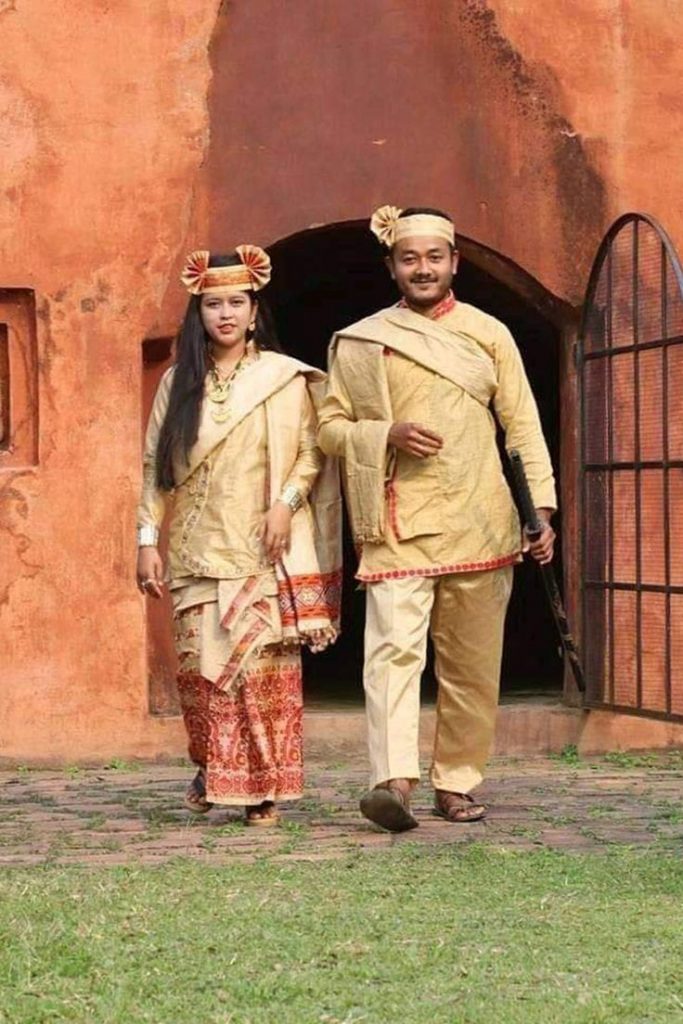

Dress and Costume

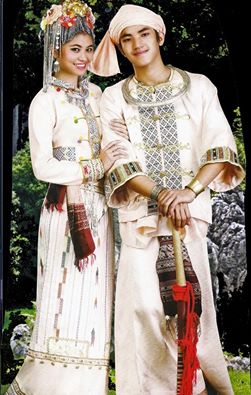

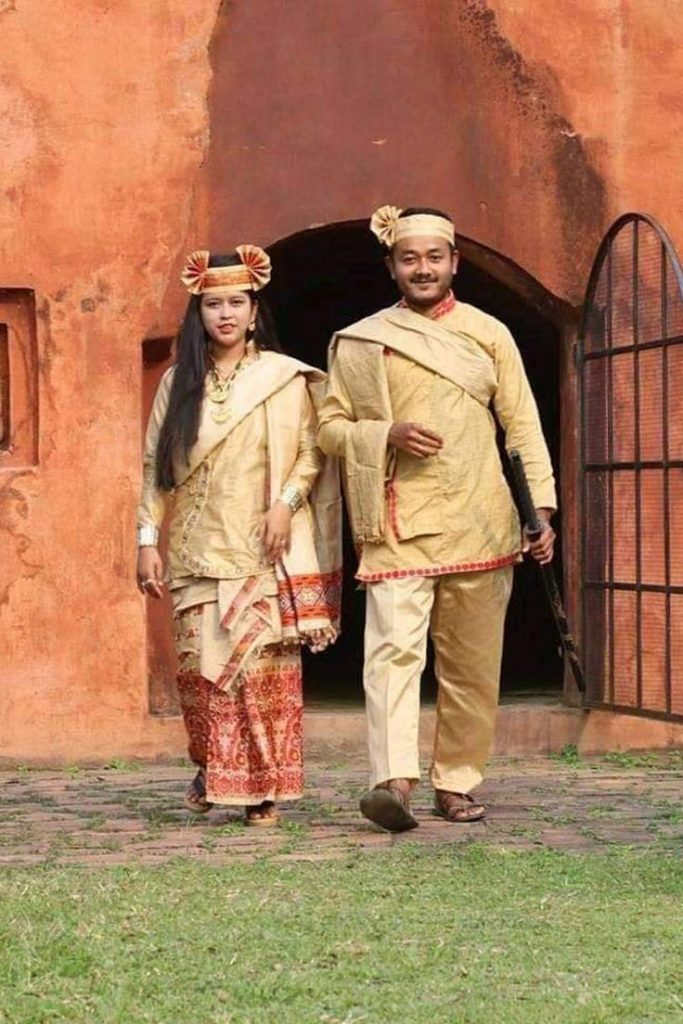

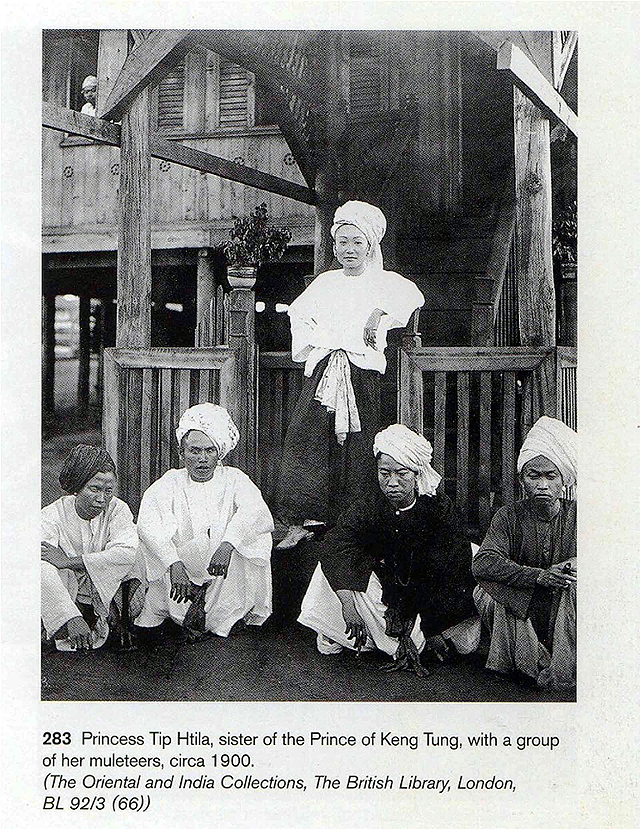

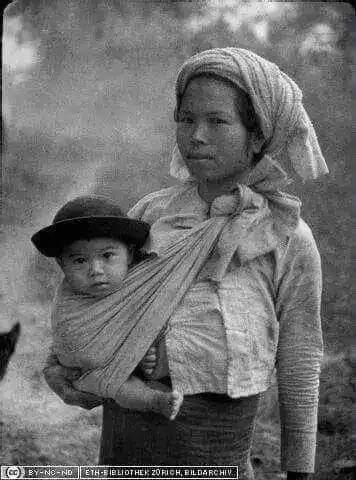

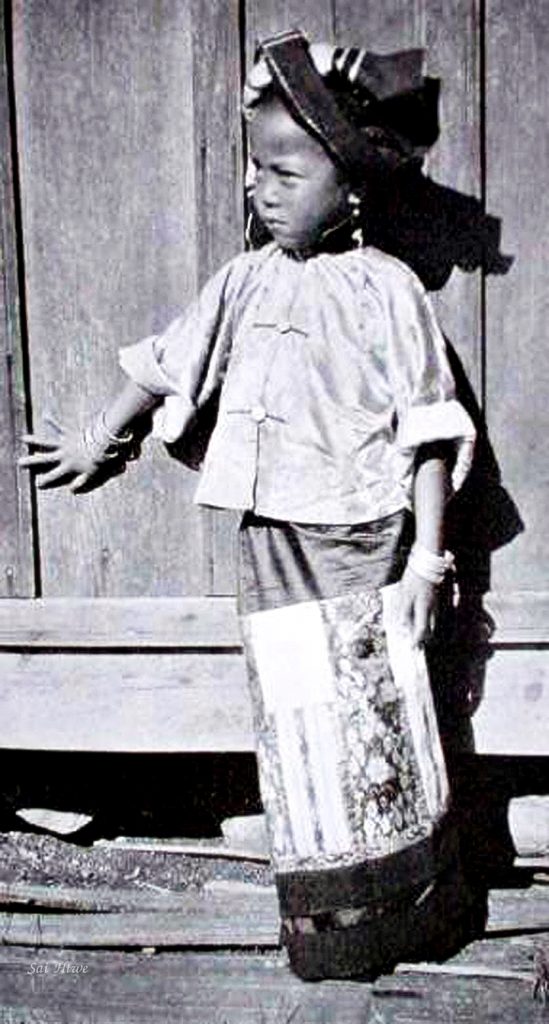

Knitting and weaving are the skills of the Shan for 2000 years. They knitted and weaved their clothes and made clothes. The original unique Tai style, its designs, patterns, and technical skill were seen in the clothing originally consisting of a woman’s skirt called “sint” (သိၼ်ႈ) and a man’s loincloth, hip wrapper long trousers. Shan trousers are very wide, and often they are made with the seat so near the ankles that they look like a shirt. The national dress of the Shan is a little bit different among the Shan living in different areas. They used to wear it on special occasions like Shan National Day, ceremonial, and festival times. The traditional woman’s sint is made up of three bands: a waistband (ႁူဝ်သိၼ်ႈ), body (တူဝ်ႊ), and lower border (ႁၢင်သိၼ်ႈ), joined at the waistband, mostly woven separately and patterned with different motifs. The body of the sint has the broadest weft dimension. Traditionally, women wear tight-sleeved short dresses and sint. Unmarried young ladies used to wear flowers in their hair and dress in colorful, shiny dresses. The elder women wear a dark blue skirt and a black turban. Many women wear a silk girdle around their waists and wind their long hair into a bun at the back of their head, fixing it with a single beautiful crescent-moon-shaped comb. Men wear collarless, tight-sleeved short jackets, with the opening at the front, and long baggy trousers in light brown color. They wear a white or yellow turban around their head. Men used to wear a headdress (turban) (ၶဵၼ်းႁူဝ်), a bag sling on the shoulder, and a sword on the other shoulder all the time. The Shan were famous for their gold and silver chased work. Beautifully designed gold and silver ornaments, bracelets, necklaces, and jewel-headed cylinders in their earlobes were worn by the wealthier classes. Nowadays, many Shan people have become more Burmanized and wear Burmese longyi. They wear their national costume on special occasions only.

Martial Art

Martial arts (လႆၢးၶႅၼ်ႉ) is also one of the Shan cultures. Most of the young men learn martial arts from their expert master. Parents encourage children to learn Shan martial arts with sword, rod, rope, and hands for self-defense, but the military government prohibits it. Old people who have learned the art used to pass it on to the younger generation secretly. Shan martial arts is not for offensive purposes but for self-defense purposes. Many modern young men do not know Shan martial arts anymore because of suppression and a lack of a trainer-master. Some masters were persecuted for teaching martial arts to young people. Some people learned secretly at night in the dark, either under a small gasoline lamp or moonlight, fearing being seen and arrested by the authorities. The master usually did not teach all the methods and secrets of the art to the learners. They used to keep at least one skill without giving it to the learners for fear that the learners would rebel against them or attack them. Shan martial arts was very similar to the Chinese martial art Wu Su. Men used to dance and show off their martial arts skills during festive celebrations.

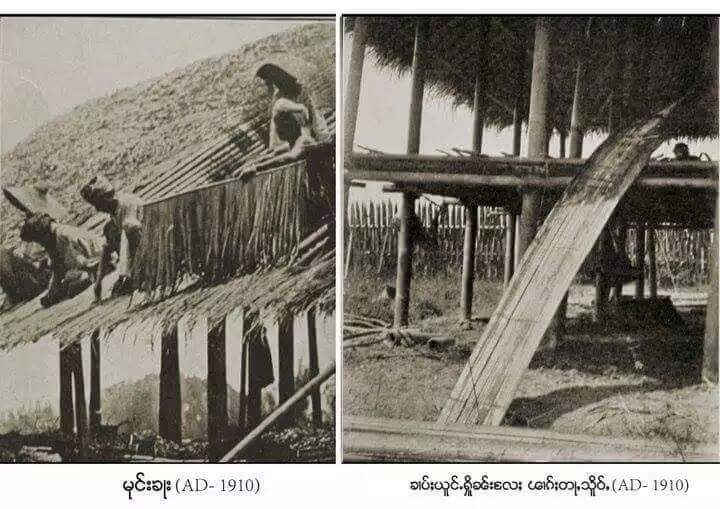

Use of Bamboo

Shan use bamboo very extensively. There are more than one hundred species of bamboo in Shanland. Bamboos are grown naturally in the forest and are easily available. It is very useful in the daily life of Shan. From the skin to the innermost part of the bamboo, nothing was left wasted. A house could be built without a single nail, but all from bamboo. No less than one hundred things can be made from bamboo. For instance, water jar, rice bowl, cooking utensils, basket, boxes, storage bins, arrow, bow, fishing rod, snare, robe, wall, written pad, cutting, spear, trap, boat, bridge, etc. Woods are also used in building houses, but it is more expensive and many people cannot afford them. Slips of bamboo twisted into string are used in fastening things. Wooden nails are used in fixing poles.

Shan are very particular when cutting bamboo. A propitious day is chosen, and the bamboos are cut on a waning moon. When they carry bamboo from the jungle to the village, they always carry it with the root-end facing the jungle so that any evil spirit, which possibly dwells in the bamboo, will be able to make good escape from the bamboo before reaching the village. On average, a Shan house built with bamboo can last ten years, but the thatch roof needs to be replaced every two years. Bamboo is never used as firewood unless it has been splintered into small pieces or powder and dried.

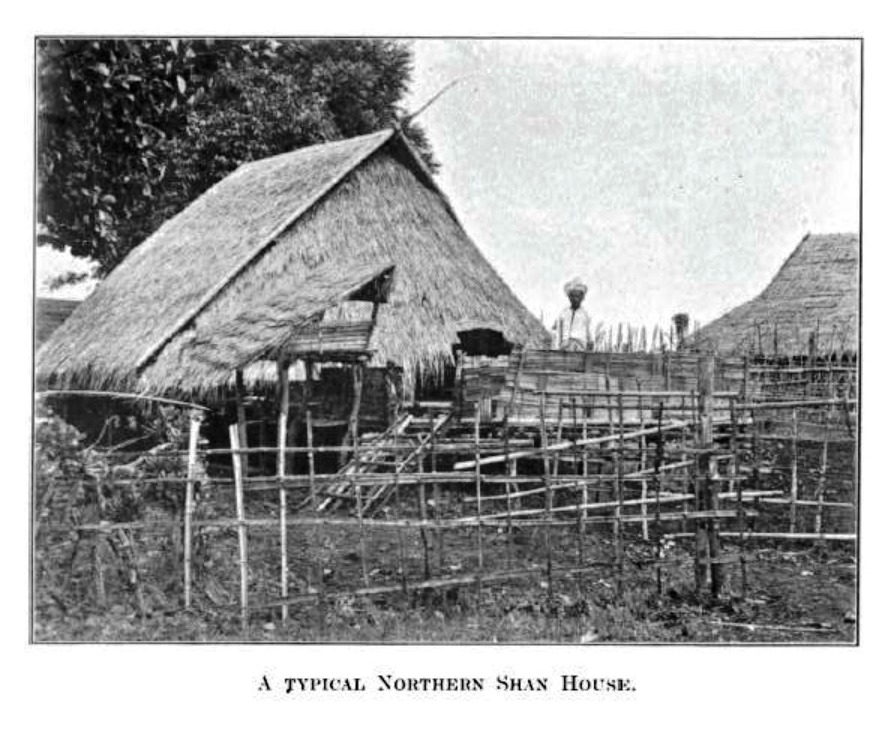

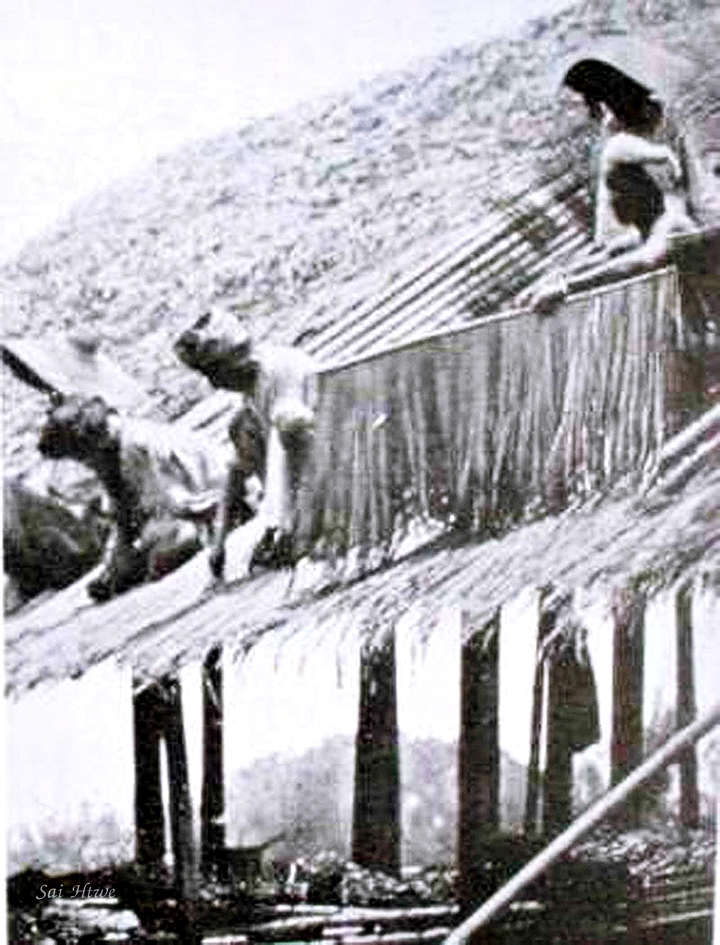

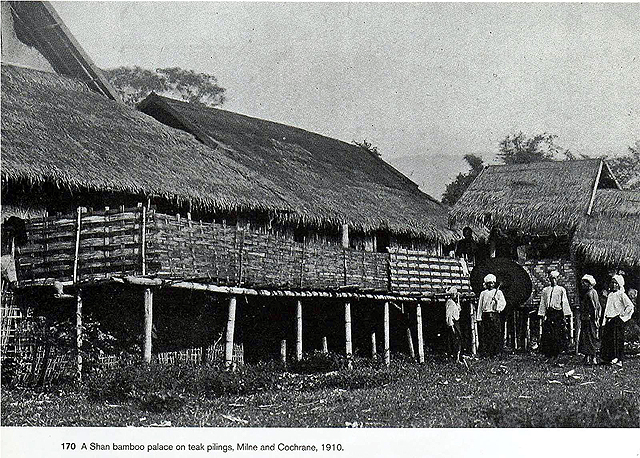

Shan House

Villagers and neighbors used to help one another in building a house. It was a very common practice. It showed unity, community spirit, love, and concern for one another. No pay was given, but meals were offered to those who helped build the house. Normally, it took only a few days to build a house for the whole village. Shan did not build their house casually. They asked the time and day of the birth of the owner (year is not important) and chose the right day and time to start building the house. They believed that if the house were built on the wrong day, not on the day of the owner, it would give the residents many problems, troubles, and even calamities. If the builder was going to build contrary to the day of the birth of the owner, more sacrifices had to be offered to the spirits to appease the spirits before building a house.[32]

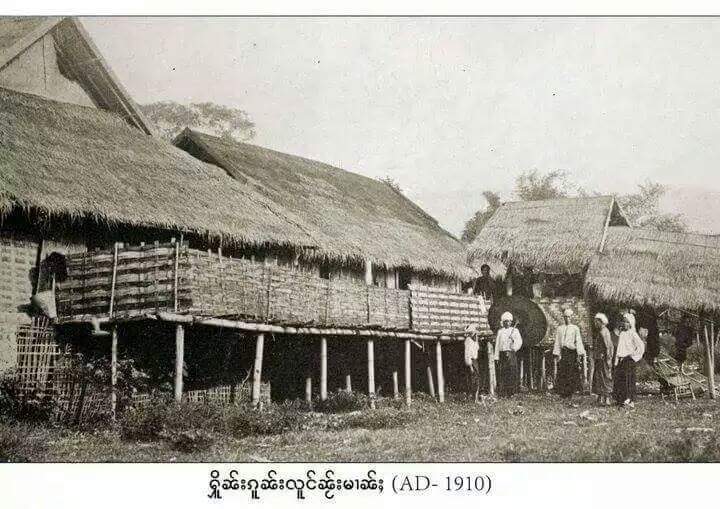

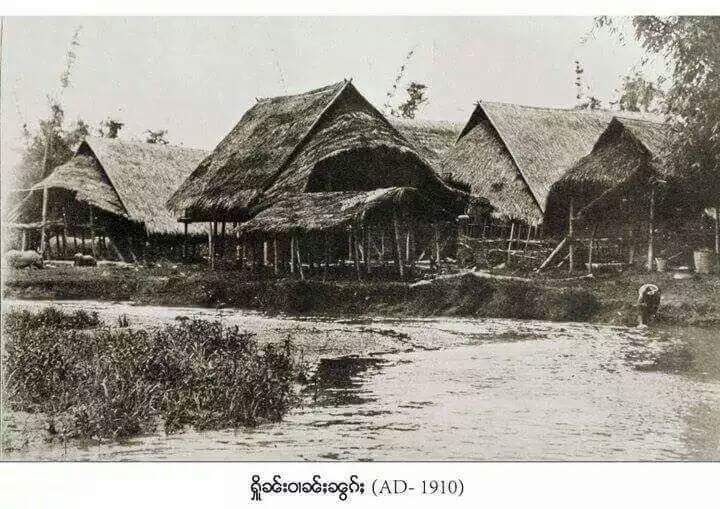

It had a peculiar regularity and neatness. The ends of the Shan houses invariably face north and south, and the edges of the roofs, leaf or thatch, were being accurately trimmed.[33] A typical Shan house had two storeys built of bamboo with a thatch roof or leaves of teak. The wall, the floor, the pillar, the table, the chair, and everything in the house were usually made of bamboo. Long grasses were naturally grown on the hillside in the forest. Such long dry grasses called thatch (ၶႃး) were used in roofing the house. The upper storey of the house was fenced with a bamboo wall. There were bedrooms walled with bamboo and a fireplace made of clay put in the middle of the sitting room. The flooring of the upper storey of the house was also made of bamboo, supported by posts forked at the top to carry the floor beams on which rest the bamboo joints for supporting the planking. The upper floor was built about six feet off the ground to avoid the ravages of white ants. The interior was divided into two, a living room and a bedroom, with an open veranda in front, particularly shaded by a fan-shaped roof, and reached by rickety steps set about eighteen inches apart. The floor and the walls were made of plaited bamboo. There was no chimney, and the smoke found its way out through cracks in the bamboo wall or thatched roof.

Mats and cushions, pillows and blankets were usually piled up in a corner during the day and set up on the floor at night to sleep. Simple mats made of fine strips of bamboo or a species of rush served as mattresses in summer and were replaced by homemade cotton mattresses in the colder months. The posts of the walls were arranged in sets of three, five, or seven, as odd numbers bring luck. The post that was believed to be occupied by the spirits “Phe” (ၽီ) was on the east side next to the corner post nearest the door. The guardian spirits of the house were supposed to occupy the portion of this post above the floor, malignant or evil spirits.[34] The spaces between each set of posts had specific names. The door of the house and the verandah were almost always at the south end. Some may put a charm on top of the main door to prevent the entry of an evil spirit. The lower part of the house was open, no walls, but pillars exposed to tie up cows or water buffalos. Animals such as buffalo, cow, pig, and chicken were placed under the house in the lower storey. Shan had the most amazing belief that buffaloes tied up for the night beneath the house were good for protection against mosquitoes because mosquitoes were attracted to the buffaloes rather than the inmates of the house. The lower compartment was also used as a storage compartment for wood, rice, or tobacco leaves. There was a step from the ground to upstairs, ascending to the verandah. The verandah was very useful for the family. They could sit and relax, have a meeting, dry up the clothes, do washing, comb their hair, or even take a bath on the verandah.

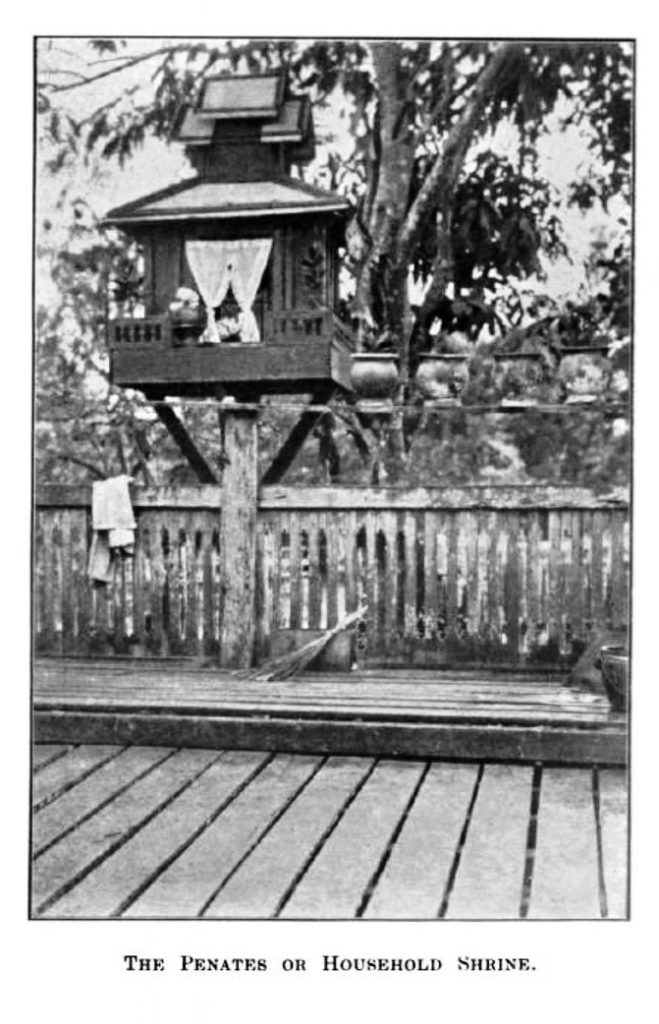

Shan used to have a home dedication ceremony before moving into the new house. No one was allowed to live in the house before dedication. It was a celebration and a feast. Monks and elders were invited to say a blessing, and neighbors and friends were invited to celebrate with a meal. At the same time, people carried blankets, pillows, mats, and other household things to the new house. When the owner of the house arrived to take possession, he was welcomed by an old man, who said, “May your home be free from all misfortunes, may you never have anxiety or sickness, may no danger come near you, and may your life be full of happiness.” After the new home dedication, the fire was lit in the entrance room, and it was not allowed to go out for seven days and seven nights. There was a high shelf built in the sitting room called “God’s Shelf.” Nothing except the Buddhist scripture, Buddha idol, and flower pots were allowed to be put on the shelf. Those who did not have a Buddha idol put the picture of the monk or pagoda instead.

Newborn and Naming a Child

In the old days, Shan women bore children by themselves through a natural process since there was no hospital. The mother or a wise woman (untrained but experienced midwife) used to give the necessary help at an infant’s birth. If labor was slow and difficult, the helper gently massaged the abdomen to assist delivery, and warm water was given to the mother to drink. The warm water was not heated on the fire in the usual way but by dropping hot stones into it. This method of boiling the water was never done in normal circumstances unless the water was to be used for medicinal purposes. The umbilical cord of the baby was severed by a piece of newly cut bamboo skin, which had been sharpened for cutting. During the birth, the husband did not stay in the room. He was, however, close at hand to take care of the placenta and umbilical cord after birth. The father first washed the placenta and umbilical cord gently, then rolled them in a banana leaf, placed them with care in a deep hole, which he had just dug under the steps of the house, and buried the placenta under the earth. It was believed that by doing it this way, it was very important for the future health and happiness of the child. It was also important that the father should wear a smiling face while he was digging the hole and depositing the banana leaf and its contents. If he, at that time, looked angry, the child would be cursed with a bad temper when he grew up. Burying the afterbirth under the steps of the house was also believed to bring more children to the family. If a child was born with the umbilical cord wrapped around his neck, it was considered a sign of great good fortune. They believed that a baby that was born with moles on any part of the body except under the eye was thought lucky. It was considered fortunate to be born with two thumbs on the same hand. After the child was born, the father and mother slept in separate rooms for two to three months. A boy would bring more gladness into the family than a girl, as all Shan believed that a man stands on a higher stage of existence than a woman.[35]

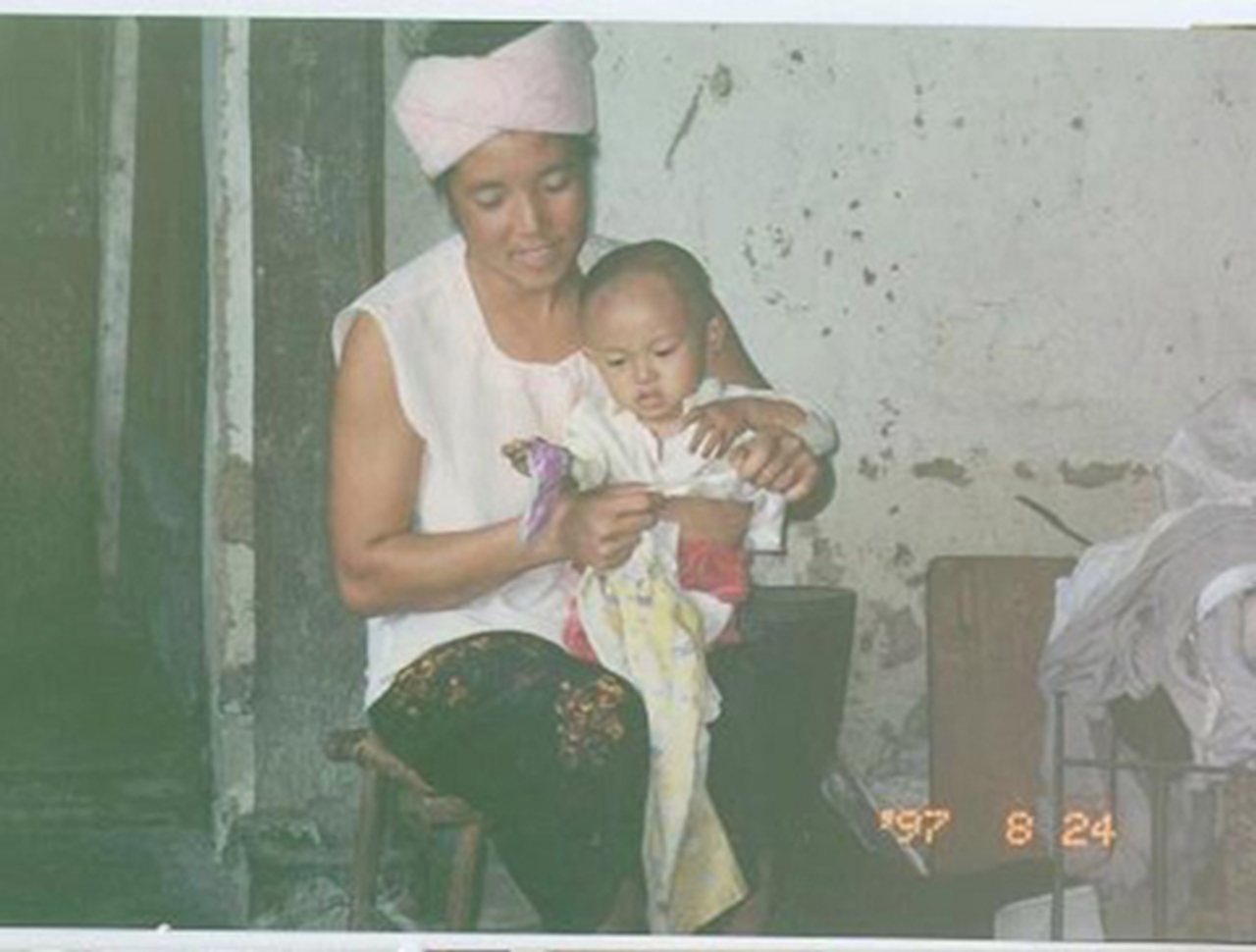

The mother washed the baby every day with clean and warm water, nursed the baby carefully, and breast-fed the baby whenever the baby cried. There was no set time for baby feeding. A newborn child was usually given a name when the child was one month old. It was a ceremony with eating, singing, dancing, and a blessing. The parents made a feast and invited their friends to be present. The food was cooked by the wise woman or helper who helped the mother when the baby was born, since the mother was not allowed to cook during the month of maternity period. When the guests arrived, they went first to a large earthenware pot, which was filled with fresh water, and into it they dropped their presents, usually a silver coin, sometimes rupees, and even gold. Then they made nice little speeches to the parents saying, “May you live to see his children’s children and may his merit be greater than ten hundred thousand moons and suns.” When all the guests had arrived and all the presents had been dropped into the pot, the water from it was poured over the baby. The wise woman put the money into the child’s hands, saying, “Now you are a full month old, may you be healthy and happy and free from the ninety-six diseases.” Then the mother washed the hands of the wise woman, and the baby was ready to receive the name. An old man or woman wound a white thread seven times round the child’s wrist and told him the name that had been chosen for him. It was believed that a white thread kept a baby safe from evil spirits. Seven was a lucky number. The coins given to the child were pierced and hung on a silver chain, which the baby wore around his neck till he/she was six or seven years old. If the coins were too many for the chain, some of them were given to a silversmith who made them into anklets or bracelets for the child to wear. The first hair, which was cut off, was very carefully kept. It was put into a little bag and hung around the neck of the baby as a sure charm to prevent him from crying in the middle of the night. If the child was ill, the bag with the cut hair was soaked in water, and the water from it was used to wash the baby’s little body, or he might have to drink it as a soothing draught.[36]

If a woman was not able to have a child because of barren she was in a deplorable state. It showed that either husband or wife, or both, had been sadly lacking in merit in previous lives. Shan were baby lovers. Cruelty to infants or children was rare. Infanticide in any form was practically unknown. [37]

Maternity Period

After giving birth, the mother had to stay in the room with the baby for one month without leaving the room. She must dress herself up in warm clothes from head to toe to prevent exposure to cold. A man usually did not go into the room within the first month after delivery because they believed that a man might lose his “spiritual power” if he went into the room who had just given birth to a baby. The mother of the baby was expected not to do any domestic work for thirty days. She did not even cook her meal. She was considered unclean during the month. Her mother or sister, or other people cooked for her and her husband. A Shan woman who had many children seldom looked old and wrinkled because of the quiet and rest time for one month after giving birth.[38]

Mother was given plenty of boiled vegetables and eggs during the maternity period, believing that she could produce more and healthier milk for the baby. A great ceremonial washing must be done for purification after one month. The process of purification was as follows:

The mother and father, the baby, the wise woman, and the friend who helped deliver the baby, together went to a running stream. First, the mother bathed herself from head to toe, standing in water, she washed her long hair for the first time in one month, carefully and thoroughly. Then she washed her baby and poured water over the hair of her husband and the wise woman. Now she was purified and considered clean, and may offer bananas and rice to the monastery and resume her normal household duties again.

Shan Name

The name could be any name given by the parents or the elder as they desired. They do not have a family surname. Sometimes, the date and time of birth were taken into consideration in giving a name. The name could be completely different from the parents’ names. For instance, the father’s name is Kham Zet, and the mother’s name is Seng Li. The child’s name can be Yuet Ngen. Yuet Ngen is the real name. Apart from the real name, a person may have a prefix before the real name.

The prefix can be the following, depending on position, class, age, etc.

Sao (ၸဝ်ႈ), Khun (ၶုၼ်), Nang (ၼၢင်း), Sai (ၸၢႆး), Maung (မွင်ႇ), Saya (သြႃႇ), Kein (ၶိင်း), Lone (လုင်း), Paw (ပေႃႊ),

Mae (မႄႈ), Pa (ပႃႈ), Nei (ၼၢႆး), Ya (ယႃႊ), Nong (ၼွင်ႉ), Pi (ပီႈ), Pu (ပူႇ), etc.

For example;

“Kham Zet” is a real name.

“Sao Kham Zet” indicates that he is from a royal family.

“Khun Kham Zet” also indicates that he is from the royal family.

“Nang Seng Kio” indicates that Seng Kio is a woman from royal family. However in modern time Nang is commonly used in the name of the ladies just to indicate that she is from Shan race, not necessarily from royal family. Nang can be assumed as racial surname for Shan girls.

“Sai Kham Zet” indicates that he is adult young person from Shan race. Sai can be assumed as racial surname for adult boys. It sometimes also means elder brother.

“Maung” is a common prefix Burmese name meaning young man. Since Shan has become more Burmanized the use of Burmese prefix is quite common.

“Saya Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is a teacher.

“Kein Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is an adult and respected person.

“Lone Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is an elderly person.

“Paw Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is respected as a father.

“Mae Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is a lady and also respectfully as a mother.

“Pa Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is an elderly mother.

“Nei Kham Zet” also means Kham Zet is an old lady.

“Ya Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is an old lady.

“Nong Sai” means younger brother, and “Nong Ying” means younger sister.

“Pi Sai” means elder brother, and “Pi Nang” means elder sister.

“Pu Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is an old man.

“Khu Kham Zet” means Kham Zet is an expert.

Almost all the name of the Shan people has the meaning. Many Shan male use to have the name in precious metal such as Seng (သႅင်) (diamond), Kham (ၶမ်း) (gold), Ngein (ငိုၼ်း) (silver) and the high things like Sun (ဝၼ်း) (Wan), Leaun (လိူၼ်ႈ) (moon), Lao (လၢဝ်) (star), etc. Shan seldom change their names in normal circumstances. Some Shan young men may change their names after their monk-hood with the prefix “Hsang” (ၸဝ်ႈသၢင်ႇ/မူၼ်ၸၢင်း).

Common traditional name among the Shan were used by serial among siblings.

As for male;

Ai (ဢၢႆႈ) (eldest son),

Yee (ယီ) (second son),

Hsam (သၢမ်) (third son),

Hsai (သႆႇ) (fourth son),

Ngo (ငူဝ်ႈ) (fifth son),

Nok (ၼူၵ်ႉ) (sixth son),

Nu (ၼူႈ) (seventh son),

Noi (ၼွႆႉ) (eighth son),

Lah (လႃႉ) (ninth son),

Lun (လိူၼ်း) (youngest or last),

Koi (ၵွႆႊ) (youngest or last),

As for female;

Ye (ယေႉ) (eldest daughter),

Ee (ဢီႇ) (second),

Ahm (ဢၢမ်ႊ) (third),

Ei (ဢႆႇ) (fourth),

O (ဢူဝ်ႈ) (fifth),

Ok (ဢူၵ်) (sixth),

Et (ဢိတ်) (seventh),

Laik (လဵၵ်ႉ) (eighth),

Lah (လႃ့) (ninth),

Lun (လိူၼ်း) (youngest or last),

Koi (ၵွႆႊ) (youngest or last).

In the old days, mother usually pierced baby’s ears when she was a few weeks old. A thread, one or two small threads, was first left in the hole. The hole was made larger and larger year by year until a small roll of cloth could be inserted. Later ornament such as silver, gold or ruby earring could be worn.

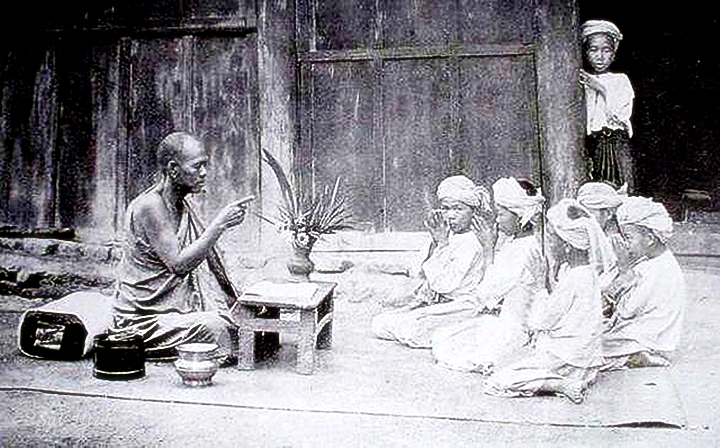

Education

In the old days, education was considered only for boys. Girls were not encouraged to go to school to get an education because their families either needed their help at home or considered them a loss and a waste when a girl got married and became a housewife. That’s why women seldom had an education. Girls usually started helping their mothers doing housework as young as six. A housewife had to stay at home, take care of the children, wash clothes, clean the house, and cook for the family. There was a common practice to send young boys to the monastery to learn to read and write Shan and chant Buddhist scriptures, as a form of schooling. Some of them became monks, while most of them returned to secular life after a certain period in the monastery. While staying in the monastery, the boys had to do all kinds of hard work, and the villagers had to bear all the financial burden of the monastery.[39] There was a Buddhist monastery in almost all villages. In the past, Shan could only learn basic education from the monastery. Christian missionaries later provided better and higher education in mission schools. Nowadays, boys and girls alike are competing in higher education because people understand the value of education. Some of the Shan are highly educated locally and abroad. But regretfully, many Shan do not know how to read and write their literature because they do not have the opportunity of learning at school. Teaching Shan at government schools is not allowed. There have been no mission schools, private schools in Burma since 1963. All private schools were nationalized by the Burmese Military Government.

A Buddhist writer claimed, “Teaching Shan literature to Shan people is not only aiming to let the people know the literature but also to make them become good people of Buddhism.”[40] The lessons included in the textbook used in learning Shan are Buddhist stories and teachings. The questions are also on the Buddhist teaching.[41] It is very difficult for Shan Christian students and students from other faiths to use Shan textbook in learning Shan.

Family

Family ties are very important in Shan. They used to have a big family. A single child in a family is very rare. They used to live together with their parents until they got married and wanted to live by themselves. Children respect their parents very much. Sometimes the parents do not want their married children to leave. They build houses in their compound for them or give them rooms to live together in their home. The son seldom goes to live with his wife’s parents (ၶိုၼ်ႈၶူၺ်), but the wife used to live with the son’s parents. Going to live with your wife’s parents after getting married is considered a poor or low status for the man and is looked down on by society.

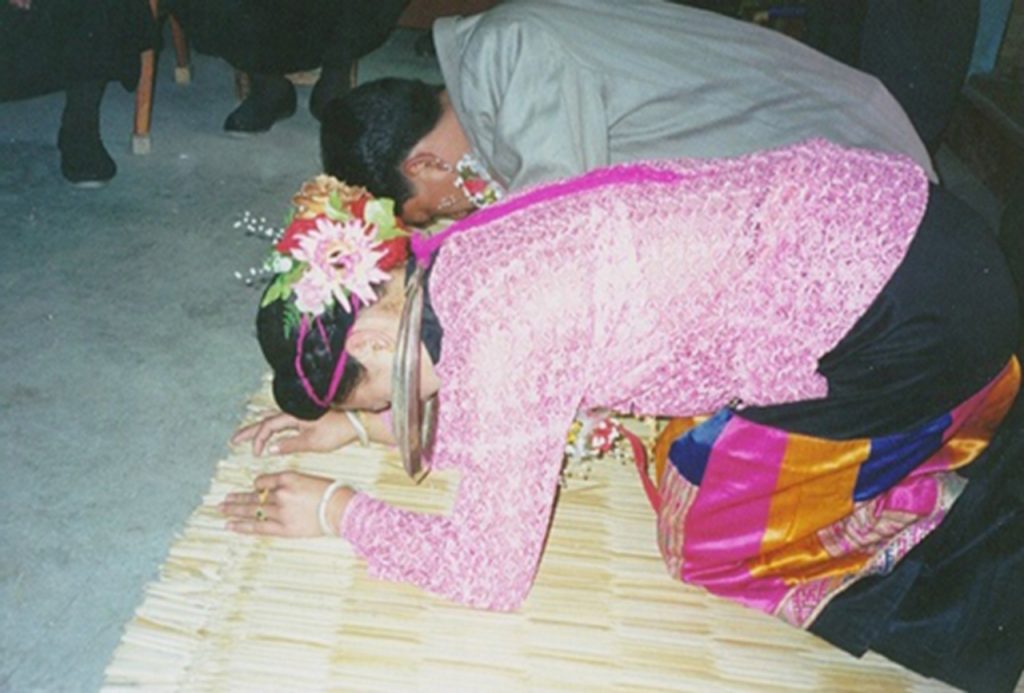

The family always dines together around the table. Children never eat before the parents and elders have eaten. Fish, pork, beef, bamboo shoots, vegetables, and curry in the pot or banana leaves were laid on the bamboo table, which was about two feet in diameter and one foot high. They used to have five to six varieties of dishes on the table. After the family has gathered round the table, the pot of steamed rice is served separately to each person by passing the pot. Members take up the rice, roll it in their hands in lumps, and eat with curry or dishes.